The Ecological Roles of Soil Cyanobacteria and Algae in Terrestrial Systems

Fundamental Distinctions and Functional Overlap. Cyanobacteria and algae are phylogenetically disparate organisms; cyanobacteria are prokaryotes, while algae are eukaryotes. Despite this fundamental difference, both groups are photoautotrophs, capable of photosynthesis. Due to their analogous ecological functions within soil ecosystems, they are often considered together in pedological and environmental studies.

Cyanobacteria: Extremophiles and Ecosystem Engineers. Formerly called blue-green algae, cyanobacteria are photoautotrophic prokaryotes that fix atmospheric CO₂, contributing significantly to the carbon cycle. They are exceptionally robust organisms, capable of photosynthetic growth in extremely arid conditions, surviving with less than 5 mm of annual precipitation and enduring multi-decadal droughts. This allows them to colonize soil surfaces across most global regions, excluding only the absolute driest deserts (see Fig. II.I, II.II, and II.III). Their tolerance to high irradiance further underscores their adaptation to the harsh, dynamic conditions of the soil surface, where light penetration is limited to the top 1-2 mm.

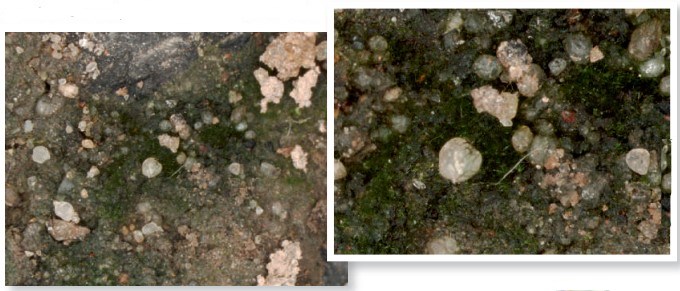

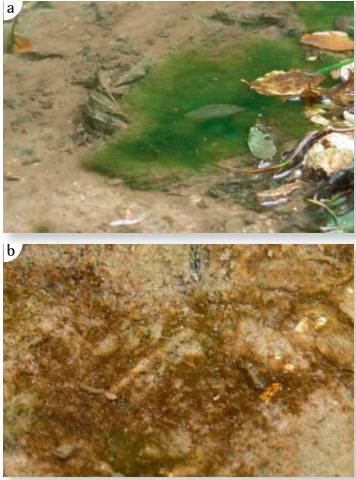

Fig. II.I: The two figures to the left depict urban soil crusts from Krakow (Poland). Figures II.II and II.III show different representations of cyanobacteria and diatoms found in one sample of soil crust

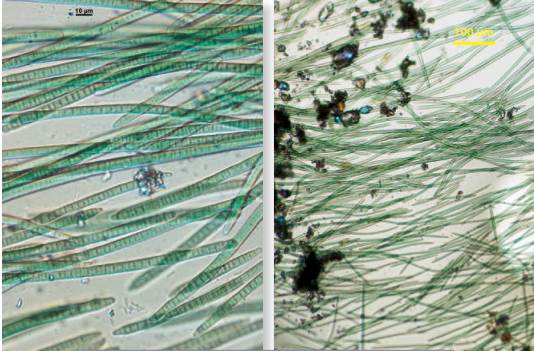

Fig. II.II: Two images of filamentous cyanobacteria, Oscillatoria sp. which can form extensive mats on urban soil such as those seen above

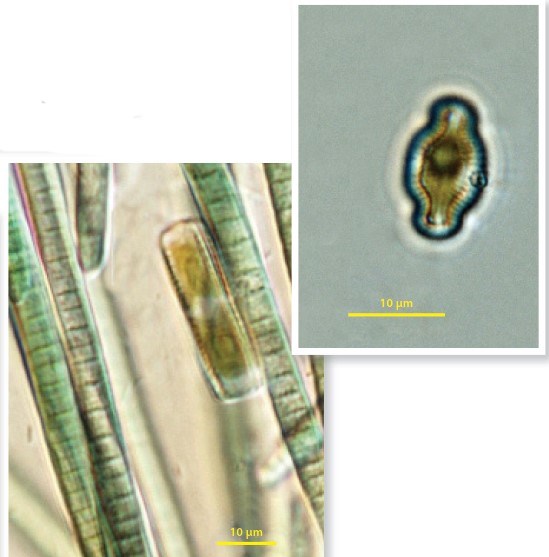

Fig. II.III: Oscillatoria sp. and diatoms from urban soil crust (left) and (right) a single, small frustule of Luticola sp.

Beyond carbon fixation, cyanobacteria are crucial non-symbiotic nitrogen fixers, playing a vital role in the nitrogen cycle (see Fig. II.IV, II.V). In systems like rice paddy fields, their nitrogen fixation is essential for productivity, with estimated rates between 10-25 kg N per hectare per year. Furthermore, cyanobacterial growth improves soil structure by reducing bulk density and enhancing water holding capacity and hydraulic conductivity.

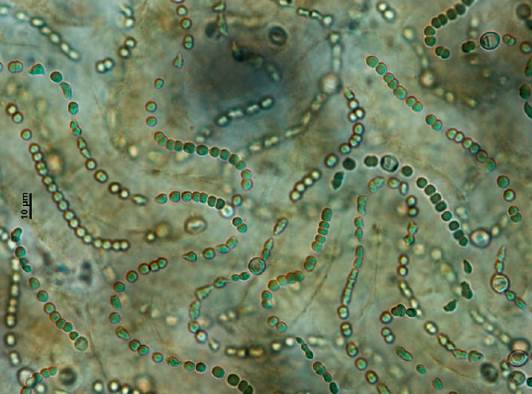

Fig. II.IV: Filamentous cyanobacterium Nostoc commune which can form macroscopic colonies on wet soil. The larger almost spherical cells which can be seen interspersed with the smaller cells are known as heterocysts which are capable of fixing atmospheric nitrogen and for moving it into the soil in a form which can be used by other organisms including higher plants

Fig. II.V: The filamentous cyanobacterium Nostoc edaphicum creates spherical colonies. As with all green photosynthetic organisms, the green colour is caused by the molecule chlorophyll and the blue tint by the molecule phycocyanin

Algae: Diversity and Distribution in Soil. Algae are ubiquitous in soils, predominantly located at or near the surface but also found in deeper horizons (see Fig. II.VI). As photoautotrophs, they require light for photosynthesis, yet numerous species—nearly 700 in some locales—have been recorded at depths of 15-20 cm. This vertical distribution is facilitated by transport via earthworms and rainwater. Motile algae, including certain diatoms and Cyanophyta, can actively migrate toward the surface if not buried too deeply.

Fig. II.VI: As with cyanobacteria, algae are also capable of forming macroscopic mats on wet soils: (a) a mat on wet soil formed by a yellow green algae (Xanthophyta) called Vaucheria sp; (b) a brown mat formed of diatoms is clearly visible.)

Ecological Functions and Adaptations. Algae are a key component of soil microflora. They act as a nutrient reservoir, incorporate organic carbon and nitrogen via photosynthesis and nitrogen fixation, influence soil structure, and regulate other soil organisms. Similar to cyanobacteria, certain algal species fix nitrogen in a light-dependent process and exhibit considerable desiccation tolerance. However, survival rates are highly dependent on drying speed, with "short and sharp" desiccation events being less detrimental than prolonged drying periods (see Fig II.VII).

Fig. II.VII: Even within taxonomic groups, algae can show morphological differences. The four pictures above all show algae from the group Chlorophyta (green algae): (a) a cell of the relatively large and spherical species Dictyococcus cf. varians; (b) the “pea like” Muriella decolour; (c) the elliptical species Chlamydomonas boldii immersed in a mucilage envelope and (d) the rod like species Stichococcus minor. All of these four species were isolated from an industrial area where the soils were polluted with heavy metals, demonstrating these species of algae to be capable of survival in relatively harsh conditions

As active constituents of biological soil crusts, algae collaborate with bacteria and fungi in mineral retention and facilitating plant succession. Over forty prokaryotic and one hundred eukaryotic genera form these communities, most frequently from the Chlorophyta (green algae), Bacillariophyta (diatoms), and Xanthophyta (yellow-green algae), with Euglenophyta and Rhodophyta (red algae) being less common.

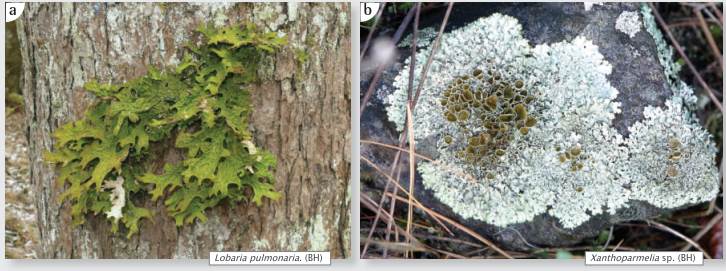

Lichens: Symbiotic Partnerships. Lichens are not single organisms but symbiotic associations between a fungal partner (mycobiont) and a photosynthetic partner (photobiont), which is usually an alga or cyanobacterium. The two are so tightly integrated they form a single morphological entity. Over 18,000 lichen "species" inhabit extreme environments from mountain tops to polar soils. They grow slowly and play a seminal role in primary soil formation through photosynthesis and the provision of organic matter upon death. Their high sensitivity to air pollution also makes them effective bioindicators of environmental health.

Date added: 2025-12-15; views: 147;