Mycetozoans (Slime Moulds): Life Cycles, Ecological Roles, and Diversity of Soil Protists

Mycetozoans, commonly known as slime moulds, are unique eukaryotic, spore-producing organisms found in terrestrial habitats worldwide. They primarily feed on bacteria and other microorganisms, playing a significant role in microbial population control. Historically misclassified as fungi, they are phylogenetically closer to protozoans like amoebae, despite being traditionally studied within mycology. The two primary groups are the plasmodial slime moulds (myxomycetes) and the less familiar, microscopic cellular slime moulds (dictyostelids). Their study often requires controlled laboratory conditions due to their cryptic life cycles and small size.

Myxomycetes: Life Cycle and Morphology. The myxomycetes possess a complex life cycle comprising two distinct trophic stages and a reproductive phase. The cycle begins with uninucleate, amoeboid cells (sometimes flagellated) that emerge from germinated spores. These cells feed via phagocytosis and reproduce through binary fission, building substantial populations in microhabitats. Under favorable conditions, these cells give rise to the second trophic stage: a distinctive, multinucleate structure called a plasmodium. This acellular, motile mass of protoplasm, which exhibits visible cytoplasmic streaming, is the defining feature of plasmodial slime moulds (Fig. IV.I).

Fig. IV.I: Plasmodium of a myxomycete

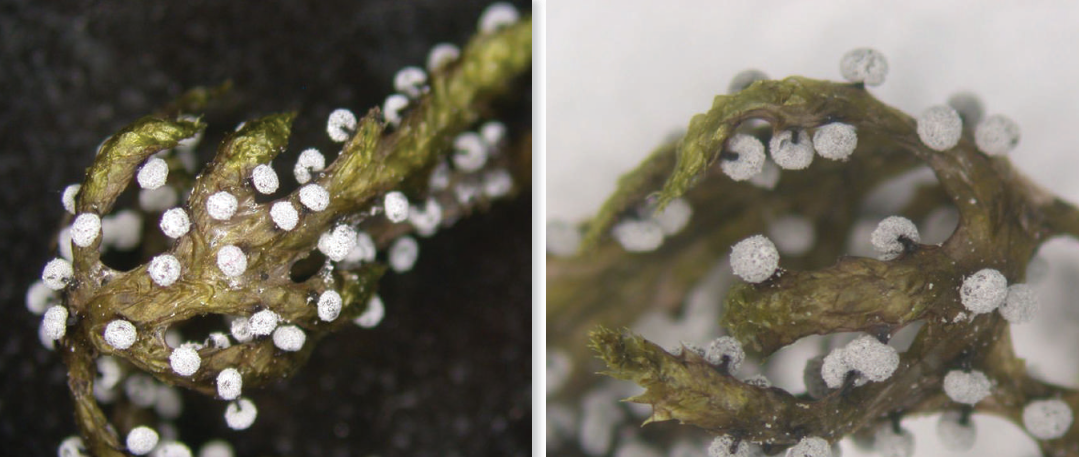

Plasmodia vary greatly in size, from a few centimeters to exceptional examples exceeding one square meter. This vegetative stage ultimately transitions to the reproductive phase, forming one or more fruiting bodies (sporophores) containing spores. Identification of myxomycetes relies almost entirely on the morphology of these often ephemeral structures and their spores (Fig. IV.II, IV.III). While typically minute (1-2 mm), some fruiting bodies can reach over half a meter. The wind-dispersed spores complete the cycle by germinating into new amoeboid cells.

Fig. IV.II: Fruiting bodies of a myxomycete

Fig. IV.III: The above two images show the fruiting bodies of myxomycetes which have formed on a moss

Ecology and Habitat of Myxomycetes. The primary microhabitats for myxomycetes are decaying wood, plant litter, and the bark of living trees. Critically, they are also abundant and widespread components of the soil biome, where they function as major predators of bacteria, yeasts, and algae. As a significant part of the soil protistan biota, they contribute substantially to active soil biomass. This prevalence suggests considerable, yet understudied, ecological importance in nutrient cycling and microbial community dynamics. Their cryptic life cycle and a scarcity of specialists contribute to their status as one of the most overlooked groups of soil organisms.

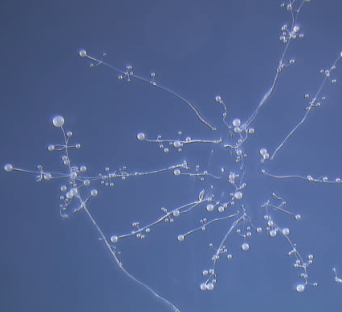

Dictyostelids: A Model of Cellular Cooperation. Dictyostelids, or cellular slime moulds, intrigue biologists with their unique life cycle, which transitions from unicellular to multicellular stages. A germinating spore releases a solitary amoeboid cell that feeds on soil bacteria. These cells divide independently until local food is depleted. This starvation trigger prompts a remarkable aggregation: thousands of cells chemotactically stream together to form multicellular clumps (Fig. IV.IV). This aggregation differentiates into a migrating pseudoplasmodium, a coordinated collective of distinct cells.

Fig. IV.IV: Aggregation of a dictyostelid

Following migration, the pseudoplasmodium undergoes sophisticated cellular differentiation. Anterior cells secrete a cellulose stalk, while posterior cells are lifted aloft and develop into spores within a fruiting body. This structure typically consists of a stalk (sorophore) bearing a terminal spore mass (sorus) (Fig. IV.V, IV.VI). The stalk cells undergo programmed cell death, sacrificing themselves to disperse the viable spores, which perpetuate the cycle. Approximately 150 species are described across the genera Dictyostelium, Polysphondylium, and Acytostelium, though molecular data suggests this morphological classification may not reflect true evolutionary relationships.

Fig. IV.V: Fruiting body of a species of Polysphondylium

Fig. IV.VI: Fruiting bodies of a species of Dictyostelium

Global Distribution and Soil Abundance. Distribution patterns vary among dictyostelid species, with some being cosmopolitan and others restricted. Biodiversity appears highest in the American tropics, suggesting a centre of evolutionary diversification; over 35 species have been recorded in a small area of tropical Guatemala. In temperate zones, diversity decreases with latitude and elevation, with a notable high of 30 species in North America's Great Smoky Mountains. Quantitative studies reveal myxomycetes are abundant in virtually all soils, sometimes constituting >50% of all soil amoebae. They are particularly prevalent in agricultural rhizospheres and grassland soils, with densities often exceeding 80 plasmodium-forming units per gram in temperate forests. Tropical forest soils remain a significant frontier for future research.

In conclusion, mycetozoans represent a vital yet underappreciated component of soil ecosystems. Their complex life cycles, ranging from the acellular plasmodium of myxomycetes to the coordinated multicellularity of dictyostelids, illustrate remarkable biological strategies. As major microbial predators, they play a crucial role in soil food webs and nutrient dynamics, warranting increased scientific attention and conservation consideration.

Date added: 2025-12-15; views: 166;