Soil Rotifers: Ecology, Reproduction, and Role in Ecosystems

Within the topsoil, leaf litter, and moss, rotifers (Phylum Rotifera) are among the most abundant microscopic animals observable under magnification (Fig. VII.I). These minute organisms, typically measuring between 0.2 and 0.4 mm, exhibit diverse locomotion: creeping, gliding, or swimming via the rapid beating of a specialized ciliary corona, a wheel-like structure that gives them their "wheel-bearer" name (Fig. VII.II). Like many soil microorganisms, rotifers require a water film for all activities. In conducive moist habitats, their population density is astonishing, ranging from approximately 32,000 to over 2 million individuals per square meter. Despite this abundance, described diversity is relatively low at around 2,030 species, though this is likely a significant underestimate due to widespread cryptic diversity—morphologically similar but genetically distinct species.

Fig. VII.I: A rotifer of the genus Macrotrachela, creeping. This genus contains many common, free-living, soil and moss dwelling bdelloids

Fig. VII.II: A rotifer of the species Macrotrachela vanoyei, feeding, showing the ciliary corona at the top of the organism

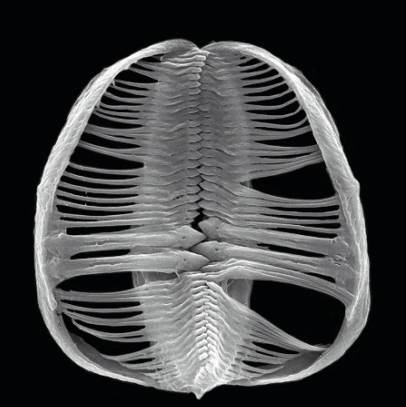

Fig. VII.III: A bdelloid rotifer of the genus Habrotrocha. With over 125 valid species recognised, this genus is one of the most diverse of all bdelloid rotifers

Soil-dwelling rotifers are divided into two major groups with distinct ecologies. The most abundant and diverse are the bdelloid rotifers (Fig. VII.III), renowned for their exclusive parthenogenetic reproduction and ability to enter anhydrobiosis. All roughly 460 known bdelloid species reproduce asexually; females produce eggs that develop into clones without fertilization, and no males or sexual reproduction have ever been observed. This makes them a unique model for studying the evolution of sex. Their second key trait, anhydrobiosis, allows them to survive extreme desiccation for decades by contracting into a dormant, barrel-shaped tun and ceasing measurable metabolism.

The second group, the monogonont rotifers (Fig. VII.IV, Fig. VII.V), is predominantly aquatic, with only a few species in terrestrial settings. Their life cycle involves alternating phases of parthenogenetic and sexual reproduction, the latter producing durable resting eggs. This combination of rapid asexual population growth and resilient dormant stages facilitates widespread dispersal and colonization. The reproductive strategies of both groups—bdelloid parthenogenesis and monogonont cyclical reproduction—fundamentally shape their global biogeography and success in transient habitats.

Fig. VII.IV: This undescribed species of terrestrial Colurella is one of several, morphologically similar and minute species of this genus of monogonont rotifer

Fig. VII.V: This undescribed species of terrestrial Colurella is one of several, morphologically similar and minute species of this genus of monogonont rotifer

The vast majority of soil rotifers are microphagous, feeding by grazing on surface bacterial films or filter-feeding on suspended bacteria, yeast, algae, and detritus within soil water. Only a few species consume larger particles, and just one known predator, Abrochtha carnivora, primarily preys on other bdelloids. Some monogononts, like Albertia and Balatro, are specialized parasites of annelids, inhabiting the body cavities of earthworms and enchytraeids, though their impact on hosts is poorly understood. Rotifers themselves are crucial prey for tardigrades, predatory nematodes, turbellarian flatworms, and large ciliated protozoans, forming a key link in the soil micro-food web.

Anhydrobiosis and Survival. During anhydrobiosis, bdelloids contract by retracting their head and foot, drastically reducing physiological activity to survive conditions lethal to most life. This state enables tolerance to complete drying, extreme temperatures, and prolonged periods—up to 20 years—awaiting rehydration. Recovery can occur within minutes to hours after rewetting, allowing them to exploit ephemerally moist habitats that exclude less resilient organisms.

Study and Identification Challenges. Studying soil rotifers is notoriously difficult. Most species, especially bdelloids, require observation of live specimens during feeding and movement to discern identifying characteristics, as their active, erratic behavior complicates examination. Consequently, research is tedious and time-intensive, which partly explains the limited knowledge of their specific ecological roles. While integral to microfaunal communities, their overall biomass is generally low, so they are not typically considered a keystone group in soil ecosystem functioning.

Commercial and Applied Uses. Rotifers have significant practical applications. Their ability to consume fine particulate waste, including dead bacteria and micro-algae (particles up to 10 micrometers), makes them valuable in aquaculture and aquarium filtration systems, where they aid water clarification and nutrient recycling. In wastewater treatment plants, rotifers play a dual role: they remove non-flocculated bacteria and enhance floc formation through mucus secretion from their corona and foot, improving sludge settlement. Furthermore, through selective grazing, they can influence the species composition of algal communities in both natural and engineered ecosystems.

Date added: 2025-12-15; views: 146;