The Ecological Significance and Biology of Soil Mites: Key Components of Global Biodiversity

Soil mites, alongside collembolans, represent the most abundant arthropods within terrestrial ecosystems. Their population density typically ranges from thousands to tens of thousands of individuals per square meter, and can even reach several hundred thousand in specific habitats. These organisms are ubiquitous, inhabiting all soil types globally, including extreme Arctic and Antarctic environments. Furthermore, they colonize diverse microhabitats rich in dead organic matter, such as peat, mosses, lichens, and decaying wood. Their ecological success is mirrored in above-ground ecosystems, where many species live as parasites on animals or plants, while others are detritivores, predators, or aquatic dwellers.

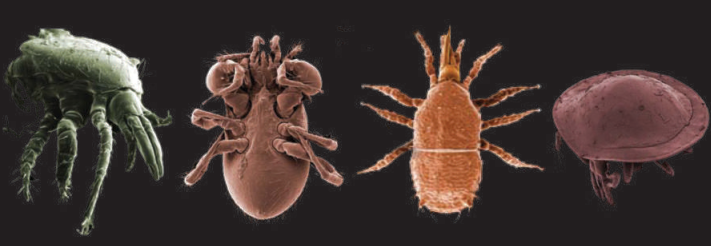

Taxonomically, mites belong to the class Arachnida, sharing ancestry with spiders and scorpions. Modern systematics suggests mites are not a monophyletic group, leading to their classification into two major lineages: Acariformes (or Actinotrichida) and Parasitiformes (or Anactinotrichida). This classification remains dynamic and subject to ongoing research. In soil environments, the Acariformes are predominantly represented by the highly diverse Oribatida (oribatid or beetle mites) and Prostigmata (prostigmatid mites). The Parasitiformes in soil are chiefly represented by the mostly predatory Mesostigmata (gamasid mites), which include the distinct subgroup Uropodina (turtle mites) (Fig. X.I).

Fig. X.I: The images show gamasid mites from different taxonomic groups. The majority of soil gamasid mites are predators, often being at the top of the soil food webs, preying on Collembola, nematodes, insect larvae or even larvae and nymphs of other mites. On the far left is a lateral view on the species Hypoaspis aculeifer. This is an approx. 2 mm long predatory species which is present in soils in Europe and which is used for the biological control of plant pests in greenhouses. Using its first pair of legs as antennae , it can detect its collembolan prey in soil by detecting odour, not only from the collembolans, but also from fungi, the prefered food of the collembolans, even recognizing the smell of the preferred food species of fungi. As well as collembolans, Hypoaspis aculeifer can feed on enchytraids as shown in Section XIX. Mouthparts of predatory species are usually raptorial, armed with multiple teeth, and often very big (as can be seen here). In the middle are two other predatory species in ventral (left) and dorsal (right) views. Specific group of so called turtle mites from the tribe Uropodina (on the far right) show a variety of feeding habits from predation or detritivory. The body is lens-like and is strongly sclerotized, with special space for attachment of legs. This protective covering most probably helps protect the species from attack by predators. Photos: left (EH), left middle and far right (JM), right middle (DW)

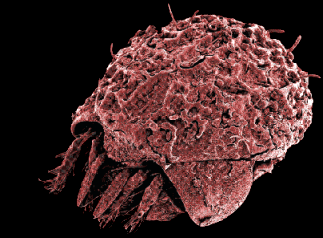

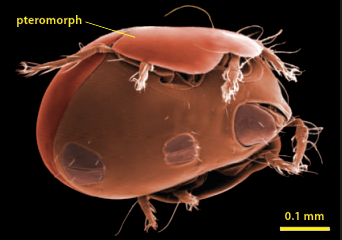

The morphology of soil mites is adapted for a life within soil pores. Adults generally possess a body size between 0.2 and 0.8 mm, classifying them as key members of the soil mesofauna. While exhibiting the arachnid trait of four pairs of legs, their body segmentation is greatly reduced or fused. A defining characteristic for many, especially oribatid mites, is a thickened, armored cuticle that provides protection against desiccation and predators (Fig. X.V). Specialized structures like pteromorphs—wing-like flaps—protect retracted legs in some species (Fig. X.VII). Being primarily blind, mites rely on sophisticated mechanoreceptors and chemoreceptors, such as sensory setae and bothridia, for navigation and feeding.

Fig. X.V: Eupelops torulosus, a species of oribatid mite which feeds by hollowing out the cells of decaying plant leaves. The body is strongly sclerotized and covered by thick irregular layer of cerotegument, which provides protection against both desiccation and predators. Ear-like pteromorphs are clearly visible on lateral side of the body, as well as lamellar structures and setae on the anterior part of the body

Fig. X.VII: Oribatid mite of genus Galumna with well developed, movable blades resempling insect wings – pteromorphes. These are nevertheless not used for flying, but for protecting body appendages

Feeding strategies among soil mites are exceptionally varied, underpinning their critical ecological roles. While some are predatory or parasitic, the majority are vital decomposers. Macrophytophages fragment larger plant tissues, whereas microphytophages (including fungivores and bacterivores) consume fine detritus and its associated microbial decomposers. This direct processing of organic matter, combined with the production of finely structured fecal pellets, directly contributes to humus formation and soil structuring. Their activity indirectly regulates microbial populations, enhancing nutrient cycling and soil health.

The development of mites is complex, progressing through egg, larval, and several nymphal stages. Reproduction showcases remarkable adaptability, with many species employing parthenogenesis, where females produce viable offspring without mating. Even in sexual species, direct copulation is not always necessary; males may deposit spermatophores for females to collect. This reproductive flexibility supports their rapid colonization of diverse habitats.

Distribution within the soil profile is heterogeneous, both vertically and horizontally. Mites are most abundant in surface layers rich in organic matter, though some species penetrate deep mineral horizons. They often occur in clusters influenced by moisture, vegetation, and organic matter distribution. Despite being slow, short-distance movers, they achieve wide dispersal through passive wind or water transport and active phoresy—hitching rides on insects, birds, or mammals.

Mites are an extraordinarily species-rich group, with over 48,000 described species and total estimates ranging from 400,000 to 900,000. In Europe, national species counts range from hundreds to several thousand, with biodiversity hotspots in the Mediterranean and Balkan regions. This immense diversity, coupled with their adaptation to virtually all feeding strategies and global environments, underscores their fundamental ecological importance.

From an anthropogenic perspective, soil mites are invaluable bioindicators of soil quality. Ecosystems deprived of their mite communities suffer accelerated degradation, losing vital functions like water retention, nutrient holding capacity, and carbon sequestration. Their immense taxonomic and functional diversity directly reflects soil health, making them prime targets for monitoring ecosystem stability and sustainability.

Date added: 2025-12-15; views: 148;