Enchytraeidae (Potworms): Ecology, Biology, and Role in Soil Ecosystems

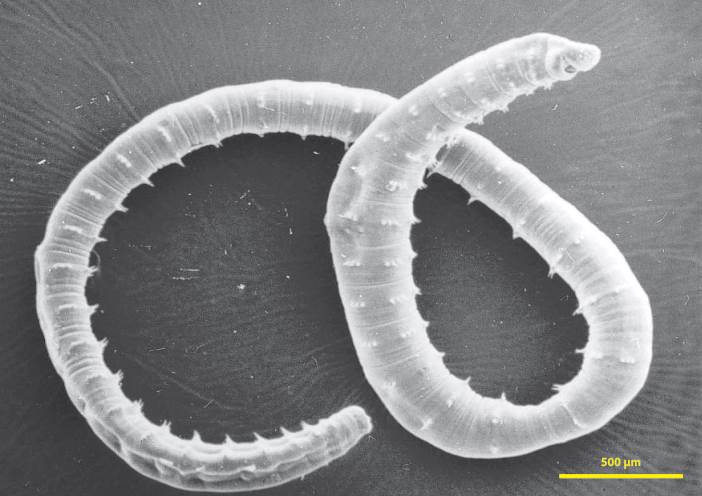

Introduction to Enchytraeidae. The Enchytraeidae, commonly termed potworms, constitute a globally distributed family within the phylum Annelida. Sharing taxonomic classification with earthworms, these organisms inhabit diverse environments including terrestrial soils, freshwater systems, and marine sediments. Typically measuring between 2 and 20 mm in length, with some species reaching 50 mm, their slender, whitish bodies classify them as soil mesofauna (Fig. XI.I). Population densities are highly variable, ranging from hundreds per square meter in arid regions to over 200,000 individuals m⁻² in coniferous forest soils. While approximately 700 species are formally described, ongoing research, particularly in understudied tropical and marine habitats, continues to expand this number significantly.

Fig. XI.I: The thin, white organism on the left of the photograph is an enchytraeid (Mesenchytraeus sp.:) laying alongside a small earthworm (Dendrobaena attemsi: on the centre/right). The image clearly demonstrates the differences in size and appearance between both related groups

Morphology, Physiology, and Reproduction. Lacking specialized desiccation protection, enchytraeids require consistently moist habitats. They maintain a critical secondary water film across their permeable skin, ensuring direct hydraulic contact with the soil matrix. These organisms are hermaphroditic, with sexual reproduction being most common, though parthenogenesis, self-fertilization, and asexual reproduction via fragmentation also occur. Species exhibit distinct ecological strategies: opportunists with rapid reproduction in nutrient-rich conditions, K-strategists adapted to stable environments with low reproduction rates, and specialists tolerant of extreme conditions like acidity or oxygen deficiency. A remarkable example are ice worms of the genus Mesenchytraeus, which inhabit glacial ice.

Ecological Function and Trophic Role. The diet of enchytraeids is relatively uniform, defining them as both saprovores and microbivores. As primary and secondary decomposers, they ingest substantial quantities of microbially colonized organic matter and mineral soil. In acidic forest soils, where earthworms are often absent, enchytraeids become the dominant agents in litter decomposition and soil mixing (Fig. XI.II). Their fecal deposits, or casts, contribute significantly to soil structure and the formation of organic horizons, though at a smaller scale than earthworm casts (Fig. XI.III). This activity is crucial for nutrient cycling and soil organic matter dynamics.

Fig. XI.II: Cognettia clarae living in the organic horizons under spruce in the Italian Alps

Fig. XI.IIb: Eggs of the species Enchytraeus albidus within a cocoon

Fig. XI.III: Casts of a geophagous enchytraeid (Fridericia sp.) deposited at the soil surface

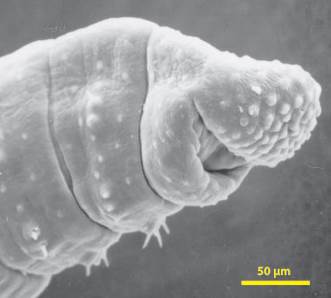

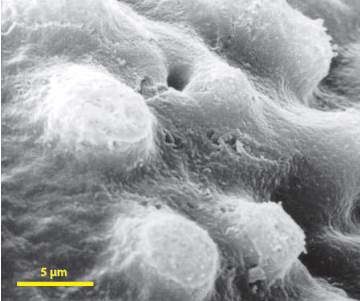

Predation, Parasitism, and Sensory Biology. Enchytraeids form a vital component of the soil food web, preyed upon by various predators including chilopods (centipedes), nematodes, mites, and beetle larvae. Predatory mites are notably significant, employing a method where they penetrate the worm's cuticle, liquefy its internal contents, and consume them (Fig. XI.IV). Parasites such as ciliates, protozoa, and nematodes are also common. Notably, pathogenic infections from viruses, bacteria, and fungi appear to increase in polluted soils, likely due to pollutant-induced stress compromising the worms' immune defenses. Despite lacking eyes, enchytraeids are photophobic and possess sophisticated chemo- and tactile receptors, especially on the head, which guide feeding, mating, and avoidance of toxins (Fig. XI.VI; Fig. XI.VII).

Fig. XI.IV: Attack of a predatory mite, Hypoaspis aculeifer, on an individual of the species Enchytraeussp. in a laboratory test vessel

Fig. XI.VI: Scanning Electron Microscopic picture of the head of the species Cognettia sphagnetorum showing a high number of chemo and tactile receptors, especially around the mouth

Fig. XI.VII: Scanning Electron Microscopic picture of individual chemo and tactile receptors located on the head of the species Cognettia sphagnetorum

Application in Ecotoxicology and Bioindication. Several enchytraeid species serve as standardized ecotoxicological test organisms. The genus Enchytraeus is particularly valuable due to the wide ecological tolerance and ease of cultivation of some species. Enchytraeus albidus, a large, easily identifiable species found in organically rich environments (Fig. XI.V), is commonly used. Smaller species like E. crypticus, with its short generation time, are also ideal for chronic toxicity and bioaccumulation tests. International organizations like the ISO and OECD have published standardized test guidelines utilizing these worms. Furthermore, enchytraeids are increasingly employed as bioindicators for soil quality assessment, especially in ecosystems like Scandinavian coniferous forests where earthworms are scarce.

Fig. XI.V: Picture of the individuals of the species Enchytraeus albidus cultured in a mixture of garden soil and cow manure. The largest individuals have a length of 1 cm.

Case Study: Cognettia sphagnetorum and Ecosystem Engineering. In acidic northern forests, the fragmenting species Cognettia sphagnetorum often dominates the soil invertebrate community, reaching immense densities. This species plays a disproportionately large role in decomposition and nutrient cycling, qualifying it as an ecosystem engineer within the mesofauna. Its asexual reproduction via fragmentation allows extremely rapid population responses to disturbances like clear-cutting. Its morphology and key identification characters are detailed in scientific illustrations (Fig. XI.VI, Fig. XI.VII, Fig. XI.VIII).

Fig. XI.VIII: Scanning Electron Microscopic picture of the species Cognettia sphagnetorum. Length of the specimen: about 1 cm

Commercial Use and Specialized Adaptations. Commercially, enchytraeids are cultured as live feed for aquarium fish due to their high nutritional and lipid content, though this same richness precludes their use as an exclusive long-term diet. The aforementioned ice worms (Mesenchytraeus spp.) exemplify extreme adaptation, inhabiting glaciers in North America. They feed on snow algae, exhibit circadian surface activity to avoid sunlight and warmth, and possess enzymes with optimal activity just below 0°C. Some hypotheses suggest they secrete antifreeze compounds. Population densities can be staggering, with estimates exceeding 7 billion individuals on a single glacier.

Taxonomic Identification and Phylogenetic Context. Accurate species identification requires expert handling of living specimens, as fixation complicates morphology. The process involves: a) observing size, habitus, and behavior under a top light; b) microscopic examination of taxonomic characters in live worms; c) detailed study of stained, mounted voucher specimens; and d) scientific illustration of key diagnostic features. Phylogenetically, enchytraeids belong to the vast phylum Annelida, which encompasses over 17,000 species of segmented worms including polychaetes and oligochaetes. They are classified within the oligochaetes, a group that also contains earthworms and leeches, and are found in virtually all moist habitats worldwide.

Date added: 2025-12-15; views: 137;