The Biology and Ecology of Nematodes: Thread-Shaped Keystones of Soil and Beyond

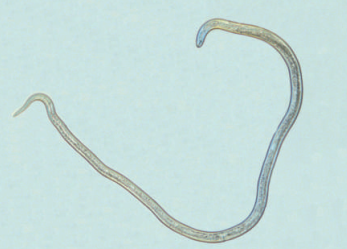

The phylum Nematoda, deriving its name from the ancient Greek for "thread-like," comprises organisms with a distinctive cylindrical, multi-cellular tubular morphology. This form encapsulates all essential organs for survival, as illustrated by the plant-parasitic Hirschmaniella genus (Fig. VIII.I). Their size spectrum is remarkably broad, ranging from microscopic dimensions (80 micrometers) to a staggering 8 meters in length for some parasitic species, with diameters from 20 micrometers to 2.5 centimeters (Fig. VIII.II). Nonetheless, the vast majority of free-living nematodes inhabiting soil and aquatic environments measure only a few millimeters. As fundamentally aquatic organisms, they reside within the thin water films coating soil particles, and they are also commonly referred to as roundworms or eelworms.

Fig. VIII.I: A nematode of the genus Hirschmaniella. All nematodes species from within this genus are plant parasites

Fig. VIII.II: A nematode of the species Pristionchus pacificus. This nematode species is being used as a model nematode in many macro and microevolutionary studies

Nematodes represent arguably the most abundant multicellular animal phylum on Earth, with population densities reaching 1 to 10 million individuals per square meter in cultivated soils. Current science describes approximately 30,000 species, yet this is estimated to be a mere 5% of the global total, indicating immense undiscovered species richness. Their extraordinary adaptability allows them to thrive in the planet's harshest environments, from Antarctic deserts and deep-sea sediments to hot volcanic springs. While many are free-living, numerous species have parasitic life cycles, utilizing plants, insects, animals, and humans as hosts, causing significant diseases such as Guinea worm and elephantiasis.

Ecologically, free-living nematodes are categorized into functional groups based on their feeding habits, primarily defined by the morphology of their mouthparts. The five principal feeding types are bacterivores, fungivores, omnivores, plant parasites, and predators. These groups serve as critical bioindicators for assessing the quality and health of both terrestrial and marine ecosystems. As keystone species within the soil food web, nematodes drive essential processes like nutrient mineralization and organic matter decomposition, profoundly influencing soil fertility.

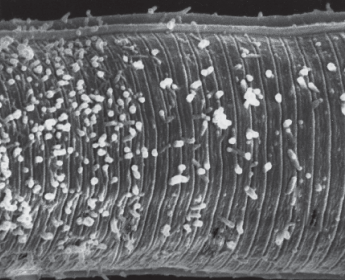

Beyond mouthpart morphology, nematode communities are analyzed using life history traits, which describe an organism's strategic response to its environment. Colonizer species exhibit rapid reproduction to exploit transient nutrient pulses, whereas persister species are characterized by long life cycles, low reproduction rates, and specialized adaptations. The composition of these functional groups is governed by environmental factors including food availability, vegetation, and abiotic conditions like soil type. Nematodes also facilitate the dispersal of microorganisms; for instance, bacteria can colonize a nematode's cuticle, using it as a transport vehicle to new food sources (Fig. VIII.III).

Fig. VIII.III: An approximately 300 μm long soil nematode colonised by about 3 μm long bacteria

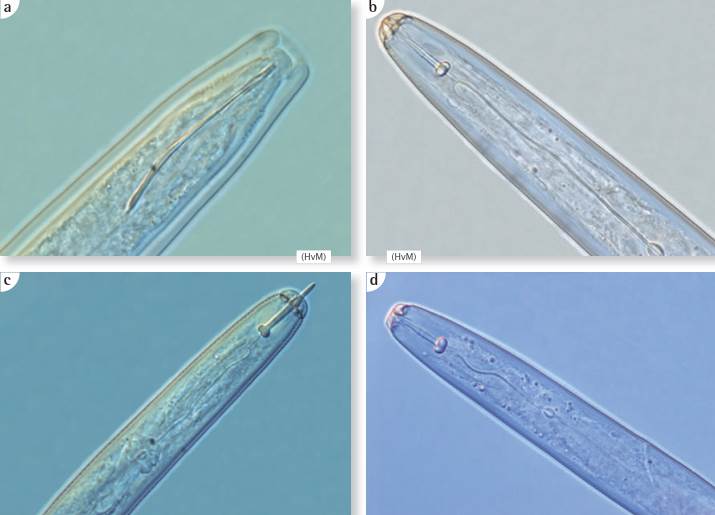

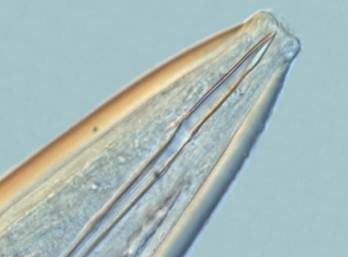

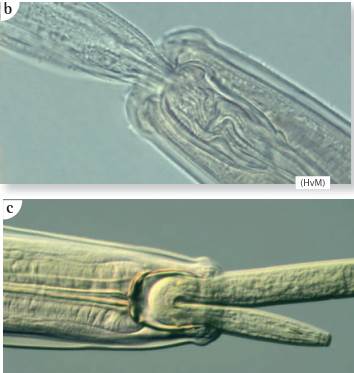

Plant-feeding nematodes are significant agricultural pests, equipped with a hollow, needle-like stylet to puncture plant cell walls and extract cellular contents (Fig. VIII.IV). Economically damaging genera include Hirschmaniella in rice, Globodera in potatoes, and Pratylenchus across numerous crops. In contrast, omnivorous nematodes like Dorylaimus sp. (Fig. VIII.V) possess a versatile hollow tooth, allowing them to function as predators on protozoa or other nematodes, or shift to feeding on fungi and bacteria depending on resource availability. Their feeding habits may also change between juvenile and adult stages.

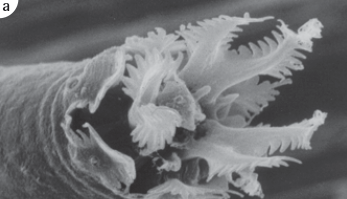

Fig.VIII.IV: Examples of plant feeding nematodes

Fig.VIII.V: Head of an omnivorous nematode (Dorylaimus sp.)

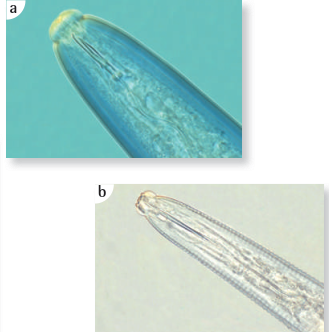

Bacterivore nematodes play a crucial role in carbon and nitrogen cycling by grazing on microbial populations. Species like Acrobeles sp. (Fig. VIII.VII a) feature anterior outgrowths called probolae, potentially used to scrape bacteria from soil particles or filter-feed. Others, such as Acrobeles complexus (Fig. VIII.VII b), possess simple tubular mouths to swallow bacteria. Emerging research suggests their grazing can stimulate plant root growth by altering microbial communities and hormone production. Fungivore nematodes, including Tylencholaimellus sp. and Anomyctus xenurus (Fig. VIII.VIII), mineralize nutrients from fungal tissue but can also impact plants negatively by consuming beneficial arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi.

Fig.VIII.VII: Examples of mouths of bacteria feeding nematodes

Fig.VIII.VIII: Heads of fungivore nematodes

Fig.VIII.IX: Heads of predatory nematodes

Predatory nematodes, representing about 5% of the soil community, consume other nematodes and small invertebrates (Fig. VIII.IX). Genera like Mononchoides and Prionchulus use powerful mouthparts to capture and ingest prey. While some nematodes are pests, most provide ecosystem services. Notably, entomopathogenic nematodes are commercially cultivated for biological pest control. They employ "biological warfare," carrying symbiotic bacteria (Xenorhabdus/Photorhabdus) inside a specialized intestinal vesicle (Fig. VIII.XI). Upon entering an insect host, they release the bacteria, which produce lethal toxins, ultimately killing the pest (Fig. VIII.X).

Fig.VIII.X: Head of the entomopathogenic nematode Steinernema

Fig.VIII.XI: Detail of the structure used by entomopathogenic nematodes, to store the infecting bacteria

Nematode resilience is exemplified by species inhabiting extreme environments. In the oxygen-deficient (anaerobic) mud layers of estuaries, genera like Tobrilus can metabolize without oxygen, functioning as partial anaerobes. In the Antarctic's McMurdo Dry Valleys, species such as Scottnema lindsayae endure mean temperatures of -20°C and minimal precipitation. This unparalleled adaptability, combined with their fundamental ecological roles, solidifies nematodes as indispensable components of global biodiversity and ecosystem function.

Date added: 2025-12-15; views: 145;