Tardigrades: The Extraordinary Biology and History of Water Bears

The scientific discovery of tardigrades, commonly known as water bears, dates to 1773. German pastor Johann August Ephraim Goeze provided the first description in his commentary on Karl Bonnet's work, noting the animal's peculiar anatomy and remarkable resemblance to a miniature bear, which inspired its initial name. Goeze also included the first known illustration of a tardigrade in his publication (Fig. VI.I). Six years later, the esteemed naturalist Lazzaro Spallanzani offered the first formal scientific description and coined the name "tardigrade," derived from Latin (tardus for slow, gradus for walker), referencing the organism's characteristically sluggish movement.

Fig. VI.I: The earliest known drawing of a tardigrade by Goeze in 1773.

Tardigrades represent an ancient lineage within the animal kingdom. The fossil record includes specimens preserved in amber from the Upper Cretaceous period, approximately 60 to 80 million years old, with another amber specimen dated around 92 million years. Even more remarkably, several fossils from the mid-Cambrian period (about 550 million years ago) have been attributed to a stem-group of modern tardigrades, indicating a deep evolutionary history. This long existence underscores their successful biological design.

The catalog of known tardigrade species has expanded dramatically with modern microscopy and exploration. From 301 cataloged species in 1972, the number grew to 531 by 1983 and exceeded 960 by 2005. Today, scientists recognize more than 1,000 different species distributed worldwide. Their habitat range is exceptionally broad, encompassing marine, brackish, freshwater, and terrestrial ecosystems from the deep sea to alpine peaks. They thrive in some of Earth's most extreme environments, including polar regions, hot deserts, and high-pressure ocean floors.

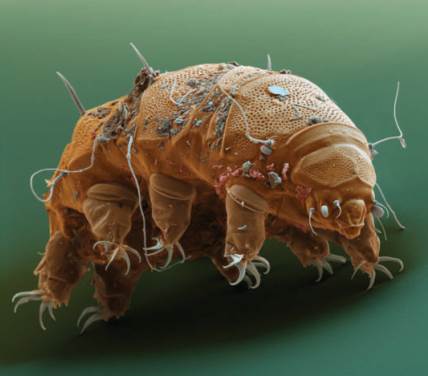

Morphology varies between habitats. Terrestrial tardigrades, commonly found in moss or lichen patches (Fig. VI.II), possess a cylindrical body up to just over 1 mm in length with four pairs of legs tipped with claws (Fig. VI.III). Marine tardigrades are often smaller (under 0.5 mm) and may feature various appendages instead of claws. While details of their feeding ecology are still being uncovered, many species are carnivorous or omnivorous. They prey on protozoans, rotifers, and nematodes by rapidly piercing them with sharp, needle-like stylets to suck out body fluids, sometimes consuming smaller prey whole (Fig. VI.IV). Herbivorous species use the same mechanism to pierce and ingest the contents of plant or algal cells.

Fig. VI.II: A tardigrade of the species Paramacrobiotus kenianus sitting on a moss leaf

Fig. VI.III: The tardigrade Echniscus granulatus has relatively long appendages and strong claws

Fig. VI.IV: A tardigrade of the species Paramacrobiotus tonollii feeding

Reproductive strategies are diverse. Though sexual reproduction occurs, direct observations are rare. Many species are parthenogenetic, where females produce offspring from unfertilized eggs, an effective strategy for colonizing new habitats. Some species deposit single eggs with intricate shells into the environment (Fig. VI.V), while others lay clutches inside their shed cuticle (exuvium). Embryonic development ranges from days to months, and individuals molt repeatedly throughout a lifespan that can vary from several months to a few years.

Fig. VI.V: An egg laid by a tardigrade of the species Marcobiotus sapiens

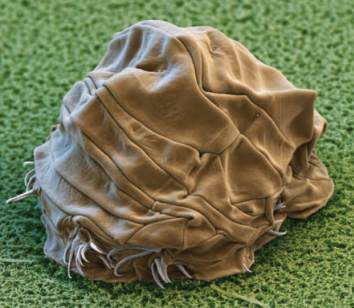

The most famed characteristic of tardigrades is their capacity for cryptobiosis, an ametabolic state of suspended animation. When faced with desiccation, they retract their legs and form a barrel-shaped structure called a tun (Fig. VI.VI). In this ametabolic state, they withstand extremes lethal to most life: temperatures exceeding 100°C or near absolute zero, intense ionizing radiation, immense pressure, and even the vacuum of space. In a landmark experiment, tardigrades survived a 10-day exposure in low Earth orbit, with many subsequently reviving and producing viable offspring. The longest documented survival in the tun state is an remarkable 20 years.

Fig. VI.VI: A tardigrade of the species Milnesium tardigradum which has entered a tun state. No signs of life are detectable while tardigrades are in this state, although they are capable of revival when environmental conditions again become suitable

Due to these extraordinary tolerances, tardigrades have emerged as a key model organism for studying biological preservation and stress tolerance. Research spans fields from astrobiology to materials science, aiming to decode the mechanisms behind their resilience. Ultimately, by understanding how tardigrades cheat death, scientists hope to uncover fundamental principles about the nature of life and its potential limits, both on Earth and beyond.

Date added: 2025-12-15; views: 129;