The Role and Classification of Soil Protozoa: Eukaryotic Microorganisms in Ecosystems

Protozoa are a diverse group of unicellular eukaryotes. The term eukaryote designates organisms whose cells contain a membrane-bound, true nucleus housing their genetic material (DNA). Beyond the nucleus, the cytoplasm of eukaryotic cells contains specialized membrane-bound structures called organelles, such as mitochondria for energy production. This complex cellular architecture distinguishes them from prokaryotic bacteria and archaea.

These microorganisms are predominantly microscopic, with typical sizes ranging from 10 to 50 micrometers, though some species can grow up to 1 mm. Protozoa are heterotrophic, meaning they acquire energy and carbon by consuming organic matter. Their nutrition involves grazing on bacteria, algae, and small fungal cells, or absorbing dissolved organic compounds from decomposed plant and animal material.

Over 30,000 species of protozoa have been identified, inhabiting diverse environments, with a significant presence in both aquatic and terrestrial systems. In soil, their population density is highly variable, influenced by factors like fertility and moisture. A teaspoon of low-fertility soil may contain only a few thousand cells, while fertile soil can harbor a million or more. Soil moisture critically determines which protozoan groups are active and predominant.

Classification of protozoa is primarily based on morphological characteristics and modes of locomotion, dividing them into four major groups. Ciliates, such as Paramecium, are covered in short, hair-like organelles called cilia used for movement and feeding (Fig. V.I, Fig. V.II). Amoeboids, including amoebae, move and feed by projecting temporary bulges of cytoplasm known as pseudopodia (Fig. V.III, Fig. V.IV).

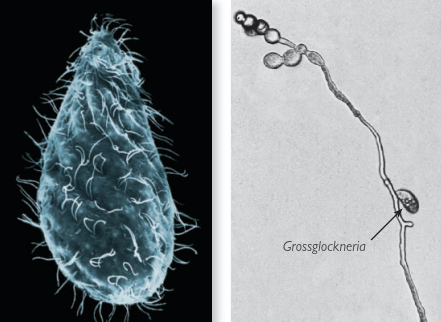

Fig. V.I: As well as the vampyrellids, other protozoa also eat fungi. The Grossglockneria acuta (above left) is about 70 μm in size and belongs to a ciliate group unique to soil known as Grossglocknerids. It has a special mouth located near the apical end and (above right) can be seen feeding on a fungal hyphae

Fig. V.II: These images show various scanning electron micrographs (with post production colour added) of soil ciliates. They range in size from <70 µm up to 600 µm, as in the case of Bresslauides discoideus (image a); images are not shown to scale. There are thousands of soil-specific ciliate species, showing a great diversity in morphology, feeding, ecology, and adaptation. For instance, the mycophagous ciliates (a) or very slender Engelmanniella mobilis (b). Some species, such as Grossglockneria acuta, are small enough to exploit the soil pores. However, large species, such as Pattersoniella vitiphila (c) and Bresslauides discoideus (a) can be found in mosses and fresh leaf litter. Some ciliates are sessile (e.g. Paracineta lauterborn (d), a predaceous species which lives in a neat, chitinous ‘shell’) although these are rare because food is quickly depleted in the soil pores. The most common soil ciliates belong to the genus Colpoda (e) and thus the soil ciliate community is called Colpodetea. The Colpoda group has greatly radiated in the soil environment, producing, inter alia, the mycophagous ciliates.

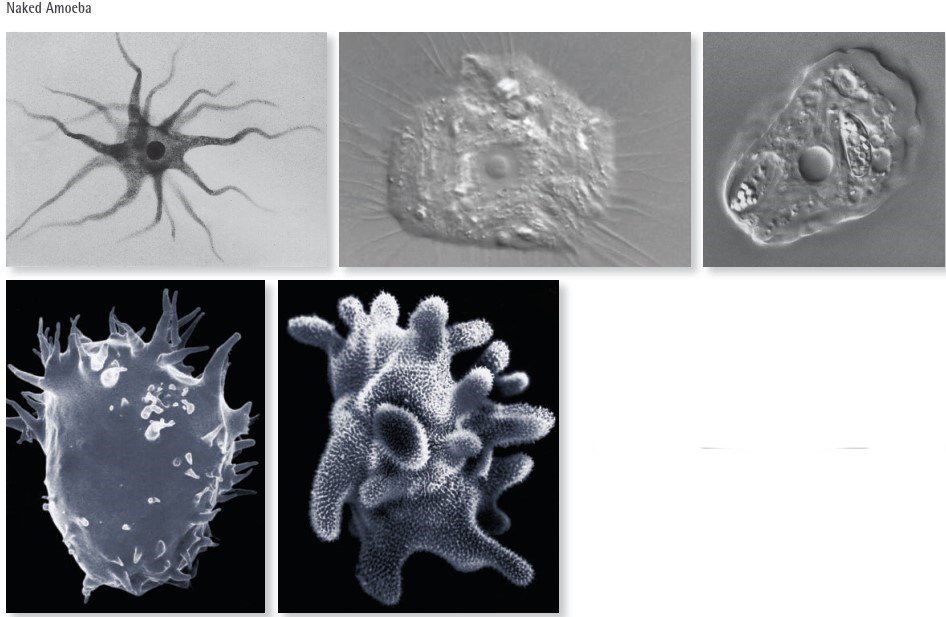

Fig. V.III: These images show various species of naked amoebae. The three above images were taken via light microscopy, with the two images to the left being taken via scanning electron microscopy, with colour added post production.

Soil naked amoebae are small, usually having a size between 10 μm and 100 μm. The cell nucleus is usually in the cell centre, being the circular structure visible in the images above left and middle.

Some amoeba have very thin and highly flexible pseudopodia, allowing them to exploit even very small soil pores (≤ 0.5 μm) and graze on the bacteria colonising the wall of the pores (upper left and middle image). However, others have thick pseudopodia, called lobopodia (lower two images), and feed on larger food items, such as fungal spores and ciliates. Naked amoebae are very numerous, i.e. there may be up to 40,000 individuals in 1 g of soil and, as such, they are important in soil energy flux

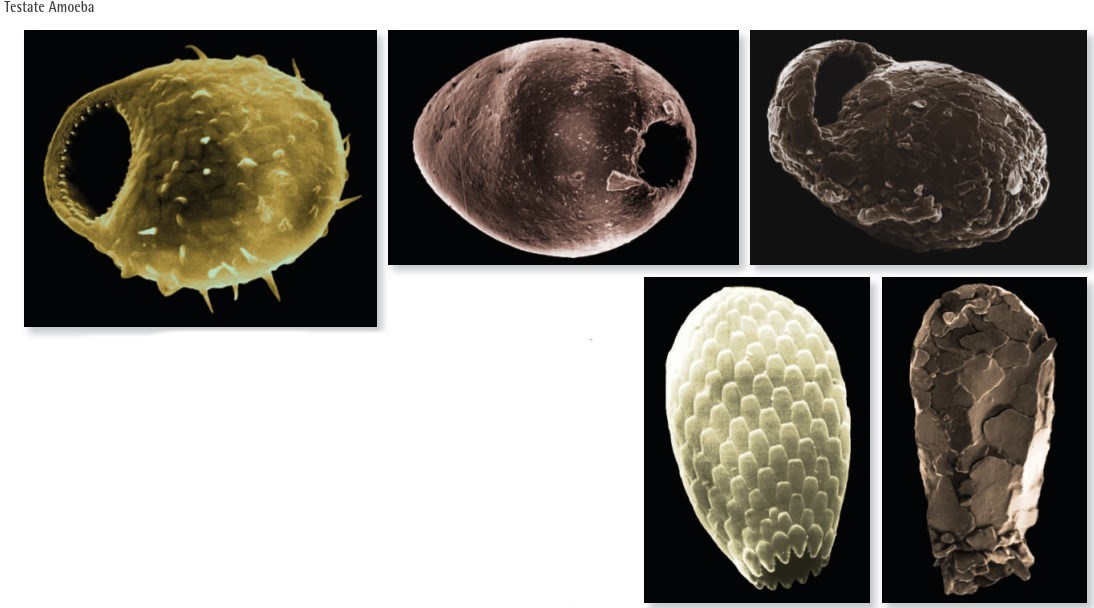

Fig. V.IV: These images show scanning electron micrographs (with post production colour added) of various testate amoebae. Their size ranges between 30 μm and 100 μm. There are usually up to 20,000 individual testate amoeba in just 1 g of soil. Testate amoebae play an important role in the energy flux of the soil and are excellent indicators of soil quality. The testate amoebae are basically similar to the naked amoebae, except of having a shell with a small opening called pseudostome. The shell is either made of siliceous platelets produced by the amoeba, as in Corythion asperulum (top left) and Euglypha (bottom left), or of mineralic particles taken from the soil environment, as in Pseudawerintzewia orbistoma (top middle), Difflugia lucida (bottom right), and Centropxsis cryptostoma (top right). The pseudostome of soil testate amoebae is often smaller than that of lake and river dwelling species to minimise loss of water. Accordingly, many of the species occurring in soil are specialised and restricted to the soil environment

Flagellates possess one or more long, whip-like appendages called flagella that propel them through their environment (Fig. V.V). The final group, Sporozoans (e.g., Plasmodium), are exclusively parasitic, spore-forming organisms that infect animals. This taxonomic framework helps in understanding their ecological roles and physiological adaptations.

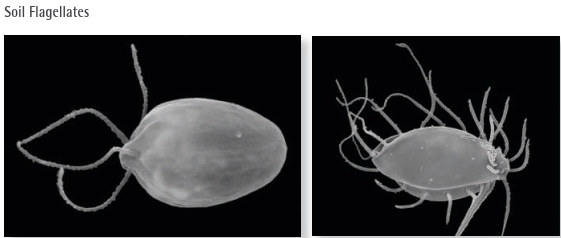

Fig. V.V: The images to the left show electron micrographs (with post production colour added) of two different species of soil flagellates, named for the long tentacle like protrusions called flagella which are used for locomotion. Polytomella sp. (left) has four flagella and is very common in soil globally. They are usually about 20 μm in size. Hemimastix amphikineta, a 20 μm-sized flagellate with two rows of flagella, occurs only in soils in central and south America as well as Australia soils, likely being a palaeoendemic, that is it probably used to exist over a much greater range which has become reduced in size over time. The fine structure of this organism is so peculiar that it has been classified in a distinct phylum, the “Hemimastigophora”

Within the soil ecosystem, protozoa function as crucial herbivores and decomposers. As primary consumers of bacteria, they act as key regulators of microbial biomass. This grazing activity is a fundamental driver of nutrient cycling, particularly for nitrogen. Bacterial cells have a high nitrogen content relative to carbon; when protozoa consume them, they ingest an excess of nitrogen.

To maintain their own elemental balance, protozoa excrete the surplus nitrogen into the soil environment as ammonium (NH4+). This process, known as the microbial loop, converts bacterial nitrogen into a plant-available form, thereby enhancing soil fertility and supporting plant growth. Their role in mineralizing nutrients is indispensable for ecosystem productivity.

Beyond nutrient cycling, protozoa are integral to the soil food web, serving as prey for larger organisms like nematodes and microarthropods. They also compete with other bacterivores, such as certain nematode species, which can lead to inverse population relationships in soil communities. Their interactions contribute to the overall balance and resilience of the soil microbiome.

The ecological impact of protozoa extends to disease suppression. Certain protozoan groups specifically prey on plant-pathogenic fungi. For example, Vampyrellid amoebae attack fungal hyphae by enzymatically drilling round holes into the cell wall, consuming the internal cytoplasm. They target significant root pathogens like Gaeumannomyces graminis, the causative agent of Take-all disease in wheat.

This predatory behavior highlights the potential of protozoa as natural biocontrol agents. Increased understanding of soil protozoan dynamics offers strong implications for sustainable agriculture and managed ecosystem health. By influencing both nutrient cycling and pathogen pressure, these microorganisms contribute directly to soil fertility, plant health, and reduced dependency on chemical inputs, underscoring their importance in agroecology.

Date added: 2025-12-15; views: 156;