The Vrable Mass Grave: Decapitated Skeletons and the Violent End of Europe's First Farmers

In 2017, archaeologists working in a Slovak wheat field near the village of Vrable uncovered four headless skeletons, a grim discovery that has since expanded into a massive find. The burials, placed in a ditch on the edge of a settlement dating back over 7000 years, belonged to the Linear Pottery culture (LBK), Europe's first farming communities. While burying individuals within settlements was common practice, systematic decapitation was not. This initial discovery has led to years of excavations, revealing an astonishingly large mass grave that challenges peaceful perceptions of Neolithic life and may explain the culture's mysterious collapse.

In 2022, researchers found more than 30 in a space barely 10 meters square (opposite page, bottom). Biological anthropologist Katharina Fuchs has also unearthed individuals buried nearby with their heads attached.

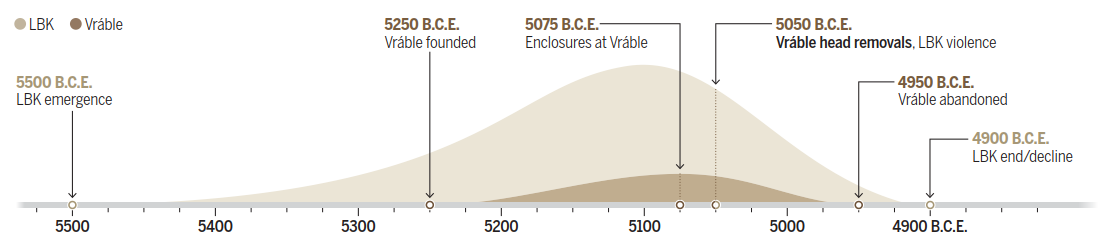

The scale of the find at Vrable is unprecedented. Researchers have now uncovered a skeletal layer approximately 45 meters long, containing the remains of at least 85 men, women, and children, almost all missing their skulls. These individuals were deposited in a communal ditch, piled two or three deep in a single, catastrophic event. According to biological anthropologist Katharina Fuchs of Kiel University, the site's relentless expansion defies initial expectations, with new bodies appearing each excavation season. This concentration of ritualized violence points to a deep societal crisis at the very end of the LBK period around 5000 B.C.E.

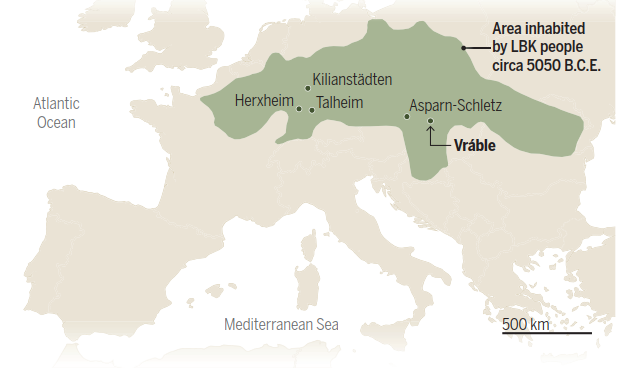

Europe’s first farmers. About 7500 years ago, farmers who traced their ancestry to Anatolia began spreading across Europe, clearing forests and founding small settlements. Known as the Linear Pottery culture (LBK), they were stunningly successful: In the space of just a few centuries, they expanded across a 1500-kilometer belt of fertile, easily tilled land.

The Linear Pottery culture represents a foundational pan-European society, descended from early farmers in Anatolia. They flourished for over 400 years, spreading across a 1500-kilometer belt of fertile loess soil from Hungary to the Paris Basin. Their settlements, characterized by large wooden longhouses, and their distinctive incised pottery show remarkable uniformity. For decades, archaeologists viewed this era as a relatively peaceful "early Eden," with little evidence of social hierarchy or specialized weapons. The proliferation of mass graves like Vrable has shattered this idyllic view, revealing a period of intense, ritualized conflict.

The wave of violence was not isolated to Slovakia. Across central Europe, contemporaneous sites like the Talheim Death Pit in Germany and Asparn-Schletz in Austria show similar patterns of mass killing, each with unique brutal signatures. At Kilianstädten, victims had their skulls and shins systematically shattered. At Herxheim, evidence points to elaborate ceremonies involving the dismemberment of hundreds of non-local individuals, feasting, and the intentional destruction of grave goods. These are not simple raids but suggest a continent-wide epidemic of ritual violence and social breakdown.

The Vrable settlement itself provides crucial context for the violence. Ground-penetrating radar reveals it was a large, densely populated hub with three distinct neighborhoods, each specializing in different livestock and showing subtle cultural variations. Shortly before the massacre, one neighborhood was abruptly enclosed by a massive, 1.3-kilometer-long V-shaped ditch and earthen berm, with gateways deliberately oriented away from the other two sectors. This was not a defensive fortification against external enemies but likely a sign of severe internal social fission and hostility within the community.

The method of killing at Vrable involved precise, gruesome rituals. Forensic analysis indicates the victims were decapitated around the time of death using small flint or obsidian knives, with cut marks evident on the cervical vertebrae. The bodies were then deposited rapidly into the ditch, as evidenced by their intact anatomical order. Curious artifacts were included in the burial, such as fist-sized river pebbles (foreign to the local loess soil) and human teeth drilled for use as pendants. The absence of skulls remains a central mystery, their removal a potent symbolic act.

Grim reapers. Over the past century, archaeologists have excavated hundreds of Linear Pottery culture (LBK) settlements, tracing the rapid expansion and often violent end of these first European farmers. Population numbers at Vráble, one of the largest known settlements, followed the same overall pattern.

Understanding the cause of this systemic violence is a primary research goal. Traditional explanations like climate change or overpopulation lack supporting evidence from skeletal remains, which show no signs of famine or malnutrition. Instead, scholars like Detlef Gronenborn of the Leibniz Center for Archaeology propose a "cultural collapse." The LBK's rapid demographic success and territorial expansion may have become unsustainable, leading to failed communication, social fragmentation, and a turn inwards, where ritualized violence became a perverse method of reinforcing cohesion or assigning blame.

In this climate of crisis, sites like Herxheim and Vrable may represent extreme ritual responses. As proposed by archaeologist Andrea Zeeb-Lanz, such violence could have been a desperate attempt to maintain social order and cultural connections in a disintegrating world. The LBK, having reached the geographical limits of its preferred loess soils, could no longer rely on constant expansion to resolve internal tensions. This pressure cooker environment, combined with growing ideological shifts, erupted in targeted, ritualized killings.

Signs of violence appear across Europe around 5000 B.C.E. At a site called Herxheim in western Germany, researchers found the smashed skeletons of nearly 1000 people, including about 500 carefully removed skull caps.

The aftermath of the violence was definitive for Vrable. Radiocarbon dating indicates the settlement was abandoned within a generation or two of the massacre, never to be reoccupied. This pattern of abandonment and cultural transition was repeated across the LBK world. While some regions remained empty for centuries, others transitioned peacefully into successor cultures. The mass graves stand as stark testimony that the capacity for large-scale, organized brutality is deeply embedded in human history, emerging even in societies without clear hierarchies or dedicated weaponry.

Current research continues to analyze the Vrable bones. Osteologists will determine age, sex, health, and geographic origins through isotope analysis where possible, despite the challenge of missing skulls and teeth. The goal is to understand the victims' relationships and the perpetrators' methods. As Christian Meyer, a paleopathologist studying the remains, notes, this violence reflects a fundamental human tendency to find scapegoats during systemic failure. Yet, as Rick Schulting of the University of Oxford cautions, the LBK's centuries of peaceful flourishing demonstrate that such violence, while always a potential part of the human repertoire, is never inevitable. The headless skeletons of Vrable are a powerful reminder of a society pushed to its breaking point.

Date added: 2026-02-14; views: 3;