Calcium Waves in Drosophila Eye Development: Mechanism for Hexagonal Ommatidial Patterning

Introduction to Compound Eye Structure and Development. Compound eyes, the visual organs found in most arthropods like insects and crustaceans, comprise hundreds to thousands of repetitive unit eyes termed ommatidia. High visual acuity depends on structural and optical factors, including ommatidial density and the precise patterning of neuronal and non-neuronal cells. While cell identity acquisition is well-characterized, the mechanisms controlling final cell positioning and shape remain less clear. In this issue, Choi et al. reveal that spontaneous calcium waves during the pupal phase in the Drosophila melanogaster (fruit fly) retina ensure each ommatidium achieves a perfect hexagonal shape and a uniform, honeycomb-like lattice across the entire tissue.

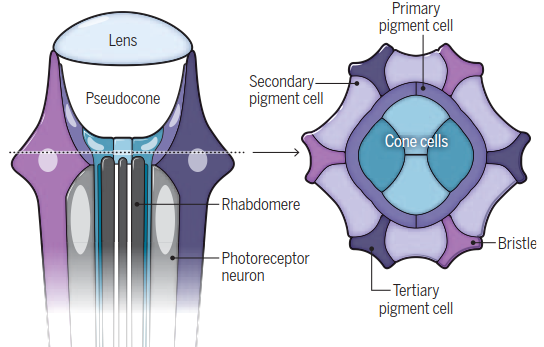

Ripples of calcium define eye structure. The compound eyes of the fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster) contain hundreds of thousands of unit eyes called ommatidia. Each ommatidium contains eight photoreceptor neurons, above which lie four non-neuronal cone cells and two primary pigment cells. These cells hold the pseudocone and are surrounded by a layer of secondary and tertiary pigment cells. Proper vision depends on the precise patterning of neuronal and non-neuronal cells, which is nalized ~40 hours after pupal formation (APF).

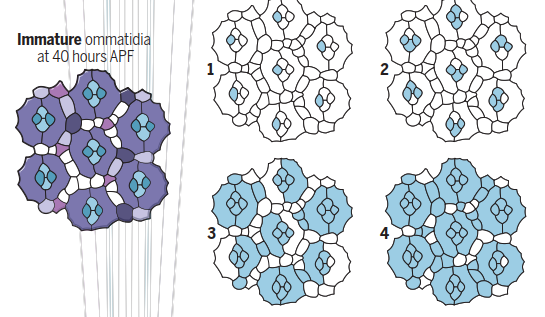

Early calcium waves. During early pupal development, spontaneous waves of calcium release trigger remodeling of the apical pro les of secondary and tertiary pigment cells to ensure that each ommatidium has a precise hexagonal shape. These waves are triggered by activation of tyrosine kinase receptor Cad96Ca, begin in the cone cells (1, 2), and spread out to interommatidial cells (3, 4).

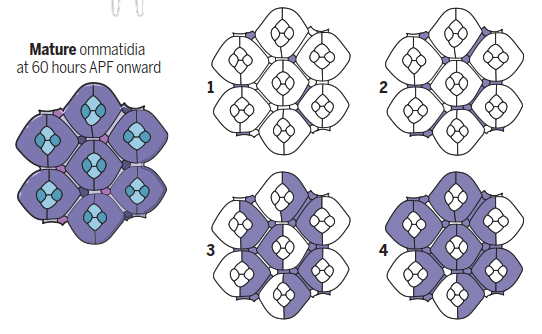

Late calcium waves. During late pupal development and early adulthood, calcium waves initiate the contraction of actin bers at the base of the interommatidial cells to form the convex shape of the eye. These waves originate in the secondary pigment cells, tertiary pigment cells, and bristles (1, 2) before spreading to the primary pigment cells (3, 4). They do not a ect the cone cells.

Cellular Architecture of the Drosophila Ommatidium. Each of the approximately 750 ommatidia in D. melanogaster contains eight photoreceptor neurons. Above these lie four non-neuronal cone cells and two primary pigment cells, which collectively surround the pseudocone (a fluid-filled cavity for light focusing) and lens. This core is ensheathed by secondary and tertiary pigment cells and mechanosensory bristles. These ensheathing cells provide optical insulation between unit eyes and create the honeycomb lattice. The mosaic pattern is established early in pupal development via waves of signaling through the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and Notch pathway, initiating stepwise specification of pigment cells. Excess cells are removed by programmed cell death, with surviving cells undergoing rearrangements mediated by a network of transcription factors, signaling pathways, and cell adhesion molecules.

Mechanism of Calcium Wave Patterning. Choi et al. demonstrate that spontaneous calcium waves are crucial for final hexagonal shaping. As cone and pigment cell arrangement finalizes, activation of the tyrosine kinase receptor Cad96Ca triggers phospholipase Cγ (PLCγ)-mediated calcium release in one cone cell per ommatidium. This initial calcium burst ripples through the ommatidium's other non-neuronal cells. The wave then propagates to neighboring ommatidia via innexin proteins, which form gap junctions (protein-lined intercellular channels) connecting cone and pigment cells. These waves ultimately activate myosin II (an actin-interacting molecular motor), remodeling the apical profiles of secondary and tertiary pigment cells to set the final hexagonal shape. Importantly, these waves refine cell shape but do not drive initial cell specification or arrangement.

Scaling of Calcium Waves in Variable Ommatidia. A critical feature of compound eyes is ommatidial size heterogeneity; for instance, ventral ommatidia in D. melanogaster are larger to enhance light sensitivity for low-light detection. The study shows that calcium wave dynamics in these larger ventral facets are precisely scaled. This scaling ensures that regardless of facet size, the exact hexagonal shape and tight packing of the lattice are maintained uniformly across the entire retina, optimizing overall optical function.

Comparative Analysis with Curvature-Inducing Calcium Waves. These findings complement prior research showing calcium waves are essential for generating the overall curvature of the D. melanogaster eye. Those later waves contract actin stress fibers in interommatidial cells, transforming a flat cell sheet into a convex eye. Key differences exist: the shape-refining waves described by Choi et al. occur early in pupal development and propagate from cone cells through the pigment lattice. In contrast, the curvature-inducing waves occur during late pupal stages, persist into adulthood, and propagate solely through interommatidial cells, excluding cone cells (see the figure).

Parallels in Vertebrate Retinal Development. Spontaneous activity waves are also initiated in the vertebrate retina. These primarily consist of action potential bursts propagating through neuronal populations like retinal ganglion, amacrine, and bipolar cells, crucial for organizing retinofugal connections. Intriguingly, calcium waves analogous to those in Drosophila propagate through non-neuronal Müller glia cells in murine and rat retinas, potentially modulating neuronal activity and synaptic strength. While not yet linked to structural fine-tuning in vertebrates, the deep structural homologies between insect and vertebrate retinas suggest a possible conserved role for glial calcium waves in cellular packing. The functional impact on visual behavior in both systems remains an open question, underscoring that calcium signaling is a fundamental property of non-neuronal cells across invertebrate and vertebrate retinas.

REFERENCES AND NOTES:

1. M. F. Land, Annu. Rev. Entomol. 42, 147 (1997).

2. B. J. Choi et al., Science 390, eady5541 (2025).

3. T. Wolff, D. F. Ready, "Pattern formation in the Drosophila retina” in The Development of Drosophila melanogaster, M. Bate, A. Martinez Arias, Eds. (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 1993), pp. 1277.

4. R. W. Carthew, Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev 17, 309 (2007).

5. T. Wolff, D. F. Ready, Development 113, 825 (1991).

6. R. L. Johnson, Molecular Genetics of Axial Patterning, Growth and Disease in Drosophila Eye, A. Singh, M. Kango-Singh, Eds. (Springer, 2020), pp. 189.

7. D. F. Ready, H. C. Chang, Development 148, dev199700 (2021).

8. B. J. Choi, Y. D. Chen, C. Desplan, Genes Dev 35, 677 (2021).

9. J. M. Rosa et al., eLife 4, e09590 (2015).

10. R. W. Zhang, W. J. Du, D. A. Prober, J. L. Du, Cell Rep. 27, 2871 (2019).

11. J. M. Tworig, C. J. Coate, M. B. Feller, eLife 10, e73202 (2021).

12. Z. L. Kurth-Nelson, A. Mishra, E. A. Newman, J. Neurosci. 29, 11339 (2009).

13. J. R. Sanes, S. L. Zipursky, Neuron 66, 15 (2010).

Date added: 2026-02-14; views: 3;