CRISPR Chromosome Fusion in Arabidopsis thaliana: Engineering Plant Karyotypes and Genome Resilience

Introduction to Chromosome Number and Karyotype Engineering. Genomic DNA is packaged into discrete chromosomes, with the number varying significantly between species. For instance, humans possess 23 pairs, while the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana has only 5 pairs. Although chromosome number is a species-defining characteristic, the evolutionary drivers and functional consequences of alterations remain largely enigmatic. In a groundbreaking study, Ronspies et al. report the successful directed chromosome fusion in A. thaliana using CRISPR technology, creating fertile plants with a reduced, eight-chromosome karyotype. This work, detailed on page 843 of Science, demonstrates profound resilience to large-scale architectural changes and establishes a foundational platform for manipulating plant karyotypes in both basic and applied research contexts.

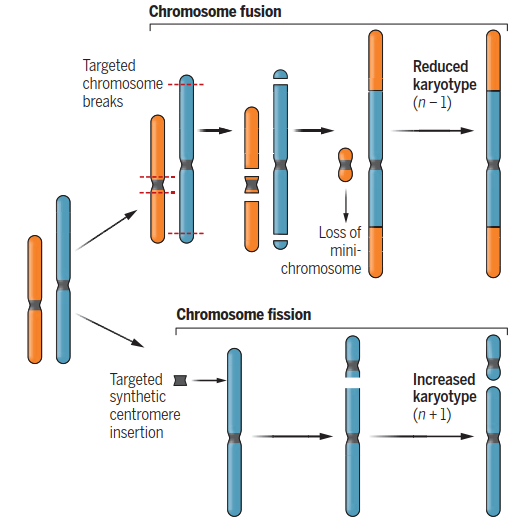

The Role of Centromeres and Precedents for Chromosome Manipulation. Each chromosome contains a centromere, a critical region recognized and bound by the cellular machinery during cell division to ensure accurate segregation. Consequently, the number of centromeres typically equals the chromosome count. Techniques for chromosome fusion have previously been established in model organisms such as yeast and mice, yielding viable offspring with fewer chromosomes. In plants, complementary strategies like chromosome fission have been achieved in maize through the installation of a synthetic centromere on a chromosome arm, effectively splitting the structure.

Methodology: Employing CRISPR-Cas9 for Targeted Chromosome Fusion. For their experiment, Ronspies et al. utilized a CRISPR-Cas9 method they had previously refined for generating chromosomal translocations and large inversions in A. thaliana. The CRISPR system creates precise double-strand breaks (DSBs) at predefined genomic loci guided by RNA sequences. The authors targeted these breaks to remove both arms of a donor chromosome (chromosome 3) and join them to recipient chromosomes (chromosome 1 or 5). The efficiency of obtaining fusion chromosomes ranged from 0.04% to 0.2% of screened progeny, aligning with prior translocation studies. Validation via fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and long-read sequencing confirmed two independent, stable lines with eight chromosomes. A minichromosome derived from the centromeric region of chromosome 3 was a transient by-product, rapidly lost in subsequent generations (see Figure 1).

Manipulating chromosome number. Chromosome fusion can be achieved through precise end-joining of targeted breakpoints induced by CRISPR, producing a reduced karyotype (n – 1) when a minichromosome is lost. Chromosome fission increases chromosome number (n + 1) by introducing a synthetic centromere at a targeted site. These complementary approaches provide a framework for both basic and applied research.

Phenotypic and Transcriptomic Resilience to Karyotype Change. Remarkably, the engineered eight-chromosome plants were phenotypically indistinguishable from wild-type counterparts across multiple traits, including growth rate, leaf morphology, root development, and seed set. Transcriptome profiling revealed that fewer than 0.5% of genes showed significant differential expression, with no enrichment in DNA repair or stress-response pathways and no perturbations near fusion junctions. This stands in stark contrast to yeast and mouse models, where chromosome number reduction triggers replication stress, growth defects, or reduced fecundity. The absence of such detriments in A. thaliana suggests plants possess exceptional tolerance for karyotype changes, potentially rooted in an evolutionary history of whole-genome duplication events and subsequent diploidization.

Alterations in Meiotic Recombination Patterns. Despite normal appearance, the plants exhibited altered meiotic recombination patterns, the process where genetic material is exchanged between homologous chromosomes. Normally, crossover events are suppressed near centromeres and heterochromatic regions and enriched on distal arms. Following chromosomal restructuring, crossovers decreased near fusion junctions and increased toward chromosome ends, independent of the original genomic context. This demonstrates a compensatory phenomenon where structural rearrangements suppressing recombination in one region elevate it elsewhere. Engineered chromosomes thus offer a model to study recombination redistribution and potentially aid breeding by unlocking traits trapped in low-recombination regions.

Natural Parallels, Speciation, and Applications in Biocontainment. Such engineered structural variants mirror naturally occurring chromosomal rearrangements that can inhibit genetic exchange between populations, acting as drivers of speciation. Changes in chromosome structure and number disrupt chromosome pairing during meiosis, essential for producing viable gametes. For example, mules are sterile hybrids due to mismatched chromosome numbers from horse and donkey parents. When Ronspies et al. crossed their engineered plants with wild-type A. thaliana, they observed a 60-75% reduction in hybrid fertility. This principle could be harnessed for biocontainment, strategically limiting gene flow between genetically modified crops and wild relatives.

Future Directions and Advanced Genome Engineering Tools. While current CRISPR-mediated structural alteration efficiencies remain modest, this study provides a crucial proof of concept. Future progress hinges on precisely controlling DSB repair. Recent advancements include inserting site-specific recombination sequences like loxP or FRT sites, recognized by Cre or Flp recombinase enzymes, respectively, enabling efficient large-scale rearrangements in rice. An emerging system using bridge RNA-guided DNA recombinases allows recombination between specific genomic loci without pre-inserted sites, offering high-precision chromosome reorganization in human cells. These tools pave the way for deliberate chromosome design, exploring minimal functional sizes and the principles governing stable transmission through cell divisions.

Prospects for Synthetic Chromosomes and Concluding Remarks. Ultimately, these efforts lay the groundwork for constructing artificial chromosomes equipped with functional centromeres, replication origins, and tailored genetic payloads. Achieving this vision will require integrating CRISPR technology, specialized recombinases, synthetic centromeres, and advanced DNA synthesis methodologies. The work of Ronspies et al. fundamentally expands our understanding of genome architecture resilience and provides powerful new methodologies for plant genetics, synthetic biology, and secure agricultural biotechnology.

REFERENCES AND NOTES:

1.M. Ronspies et al., Science 390, 843 (2025).

2. J. Luo, X. Sun, B. P. Cormack, J. D. Boeke, Nature 560, 392 (2018).

3. Y. Shao et al., Nature 560, 331 (2018).

4. L.-B. Wang et al., Science 377, 967 (2022).

5. Y. Zeng, M. Wang, J. I. Gent, R. K. Dawe, Sci. Adv. 11, eadw3433 (2025).

6. N. Beying et al., Nat. Plants 6, 638 (2020).

7. M. Ronspies et al., Nat. Plants 8, 1153 (2022).

8. J. F. Wendel, D. Lisch, G. Hu, A. S. Mason, Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 49, 1 (2018).

Date added: 2026-02-14; views: 3;