Neural Organoids: Brain Models, Ethical Implications, and Future Research Directions

Introduction to Neural Organoids. Derived from human stem cells cultured with specific molecular signals, neural organoids, often called brain organoids, can form simplified three-dimensional structures resembling regions like the cerebral cortex or cerebellum. Typically measuring a few millimeters, these models are not fully functional "brains in a dish," yet they increasingly replicate the cellular diversity and layered architecture of the developing human brain. This rapid scientific advancement allows unprecedented study of neurodevelopment and disease. As noted by sociologist John Evans of UC San Diego, the field's progress in just the past year is both surprising and striking, highlighting its accelerating sophistication.

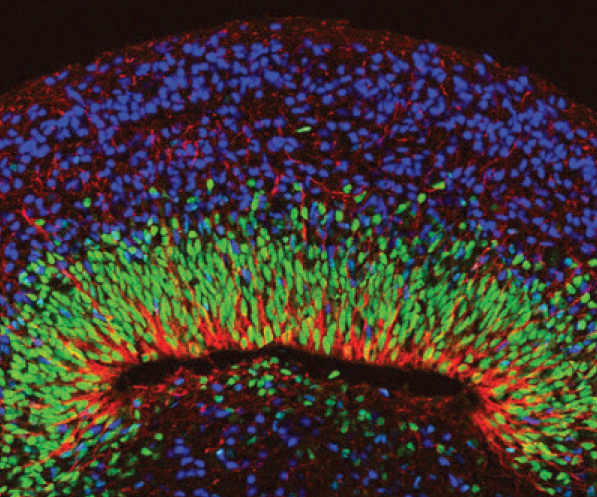

Neural organoids made from human stem cells can mimic the natural layers of the brain and help model diseases.

Scientific Promise and Ethical Questions. This progress provides powerful tools for investigating normal brain function and disorders, but it simultaneously intensifies profound ethical debates. Researchers must consider whether these assemblies of human neurons could possess a capacity for pain, intelligence, or even a form of consciousness. Additional concerns include the morality of transplanting organoids into animal or human brains and the potential for such research to challenge fundamental definitions of humanity. These questions formed the core of a recent gathering of scientists, ethicists, and advocates at the historic Asilomar Conference Grounds in California.

The Asilomar Conference and Governance Discussions. The conference site was chosen for its legacy, echoing a seminal 1975 meeting that established early guidelines for genetic engineering. Co-organizer Henry Greely, a Stanford University law professor, clarified that the goal was not to create new rules but to review the science and consider governance frameworks. Participants deliberated whether an existing body, like the International Society for Stem Cell Research (ISSCR), or a new organization should monitor advances and provide necessary oversight. A consensus emerged on the imperative to include public dialogue in ongoing ethical discussions, although no prescriptive conclusions were reached.

Modeling Diseases with Brain Organoids. Neural organoids offer a transformative platform for modeling neurological diseases and developmental disorders. Neuroscientist Guo-Li Ming from the University of Pennsylvania presented work using organoids to study viral impacts. Her team demonstrated that the Zika virus targets and inhibits neural progenitor cells, explaining linked microcephaly. In recent preprint research, they found the Oropouche virus, spreading in Latin America, similarly disrupts these progenitor cells. Such studies underscore the utility of organoids in deciphering disease mechanisms that are difficult to study in vivo.

Enhancing Complexity with Assembloids. Researchers increase model complexity by creating assembloids, which interconnect multiple organoids. Sergiu Pasca, a Stanford neuroscientist and conference co-organizer, published a Nature study creating four distinct neural organoids representing different brain and spinal cord regions. When linked and stimulated chemically at one end, a signal propagated to the opposite end, demonstrating a functional sensory pathway. This advancement raises direct questions about sentience, such as whether assembloids can feel pain, though Pasca notes they lack the necessary secondary pathway for the subjective experience of pain.

Translational Research and Animal Models. Pasca’s team is pursuing treatments for Timothy syndrome, a rare genetic disorder causing heart arrhythmias and neurodevelopmental symptoms. Using patient-derived neural organoids with a specific calcium channel mutation, researchers identified antisense oligonucleotides that reduced levels of the defective protein. Lacking an animal model, they implanted human organoids into rat brains to test the therapy, finding it effective. This approach exemplifies the potential translational payoff of organoid research, bridging in vitro modeling and pre-clinical testing.

Public Perception and Ethical Boundaries. Transplanting human cells into animal brains historically causes public unease. John Evans’s surveys indicate many find such cross-species implantation objectionable, viewing it as a boundary violation. However, the pressing need for novel medical treatments may outweigh these concerns for oversight bodies. This tension between ethical caution and therapeutic imperative remains unresolved, highlighting the need for transparent guidelines as research progresses toward clinical trials.

Pathway to Clinical Application. Pasca announced plans to seek approval for a clinical trial next year, testing an antisense oligonucleotide for cognitive symptoms of Timothy syndrome. This would mark the first potential psychiatric treatment developed via neural organoid research. Alison Singer, president of the Autism Science Foundation, which funds such work, emphasizes the urgency for therapies and hopes ethical discussions yield concrete action. Patients and families depend on this research momentum, urging scientists to establish clear ground rules without undue delay.

Critiques of the Ethical Dialogue. Some ethicists critique the framework of these discussions. Ben Hurlbut of Arizona State University, in a Science commentary, criticized the "science first, ethics second" pattern of Asilomar-style meetings. He argues experts often set standards autonomously, presenting them as a fait accompli and stifling broader debate. While he acknowledged conference participants were asking pertinent questions, he warned against repeating this exclusionary habit, advocating for more inclusive and anticipatory ethical engagement from the outset.

Conclusion: An Evolving Landscape. The future of neural organoid research is poised between extraordinary potential and significant ethical uncertainty. As the science continues to advance, creating ever more accurate and complex models of the human brain, the questions of oversight, public consent, and moral limits become increasingly urgent. The community has not yet determined the definitive path forward. The central challenge, as Evans notes, is deciding "what we are going to do next, and that’s not clear," underscoring that navigating this frontier remains a critical work in progress.

Date added: 2026-02-14; views: 5;