A Biocultural Framework for Language Evolution: Case Studies and Insights

The origins of human language, a defining trait of our species, remain profoundly enigmatic. The absence of a direct fossil record and numerous unknowns regarding human evolution and animal communication have led some to deem the question scientifically intractable. Contrary to this view, we argue that the study of language evolution is firmly within the realm of scientific inquiry when integrating novel data sources and theoretical perspectives. This article presents an empirical biocultural framework for such research, applying it to three focused case studies that examine distinct facets of language. Our objective is not to exhaustively review existing theories or promote a singular one, but to establish an agenda for future interdisciplinary work by highlighting the most promising research avenues.

This approach is inherently multifaceted, treating language emergence as the convergence of multiple capacities—physical, cognitive, social, and cultural—each with its own developmental and evolutionary trajectory. Key facets include the production and perception of signals (e.g., vocal learning), the systematic organization of linguistic structure, and the underlying communicative motivations (e.g., social behavior). A facet need not be uniquely human or linguistic to hold explanatory power; similar to other complex biological systems like the eye, language likely arose through modification, recombination, and exaptation of ancestral infrastructures. This perspective moves decisively away from simplistic "silver bullet" theories, which attribute human distinctiveness to a single factor like a genetic mutation, views that are untenable given modern biological understanding. Substantial evidence confirms that no solitary phenomenon was sufficient to "give us language".

Consequently, the multifaceted perspective demands empirical investigation across extended historical windows. While traditional views often confined language to anatomically modern Homo sapiens within the last 50-150 thousand years (kyr), contemporary data suggest deeper evolutionary timescales of hundreds of thousands or even millions of years are more plausible. Even if the fully modern language system is a recent development, its constituent facets likely evolved over vastly longer periods under diverse selective pressures. Our framework is also fundamentally biocultural, recognizing the interplay between biological preparedness and cultural processes as central to language emergence. Understanding innate learning mechanisms and biases is crucial for explaining human distinctiveness and guiding comparative research with nonhuman species.

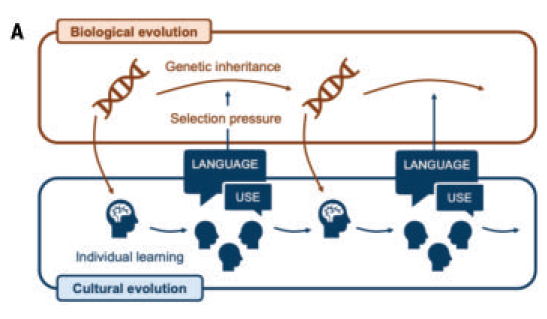

However, no human infant develops a structured language in isolation; it arises only through extended social interaction and cultural transmission. Over generations, learners progressively systematize language through communication, a process shaped by individual and community properties. Computational simulations and empirical studies show specific cultural processes are necessary for structured language to emerge. A key reason other species lack human-like language may be insufficient biological capacity to support these cultural processes. Critically, biology and culture interact in complex ways; for instance, more complex communication can increase selective pressure on the cognitive mechanisms needed to learn it. This can create virtuous cycles of gene-culture coevolution (Fig. 1), making iterative biocultural processes essential for understanding language origins. Both biological and cultural phenomena, along with their interactions, are empirically investigable in humans, animals, and artificial agents.

Fig. 1. Gene-culture coevolution model. Interacting processes operating on different timescales, from milliseconds to millennia, shape language emergence. (A) Processes of language use operate at the shortest timescale, as individuals comprehend and produce utterances in ongoing conversation. Learning to form these utterances (learning sounds, words, and rules) happens over a lifetime of exposure to the language of the community. Zooming out further, the structure of a specific language emerges and changes through cultural evolution, as knowledge of language is passed from one generation to the next. Lastly, the cognitive and anatomical machinery that allows humans to learn and use language has been subject to genetic evolution over the course of human evolution.

The processes of biological and cultural evolution interact to produce a dual- inheritance system. Features of languages are inherited culturally, and the mechanisms that support such cultural inheritance are themselves inherited genetically. These processes may interact in complex and interesting ways, studied using mathematical and computational models that include all three timescales: individual learning and use, cultural evolution, and biological evolution.

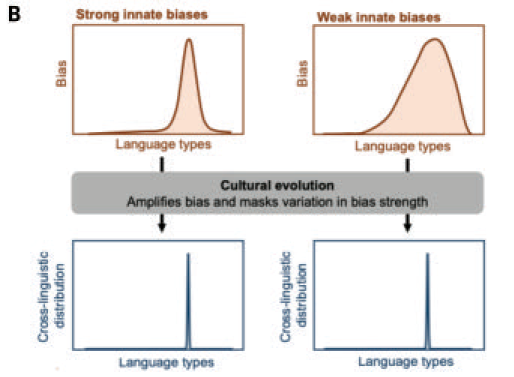

(B) One prominent approach, iterated Bayesian learning, treats learning as a process of inductive inference, combining utterances that the learner observes with a prior bias favoring particular types of languages. Cultural evolution is modeled as a process in which the languages inferred by one generation provide data observed by the next generation of learners. Iterated Bayesian learning allows us to compute expected results of cultural evolution for any hypothesized prior bias learners might have along with a model of how language is used for communication.

This approach has been extended to the full dual- inheritance model by assuming that priors for learners are shaped by their genes, and these genes are selected based on communicative effectiveness of the individuals in the population. One notable finding is that the existence of cultural evolution tends to weaken inductive biases in language learning. Cultural evolution amplifies weak biases in individual learners, such that weak biases have the same outcome at the population level as strong constraints would. If strong biases are costly to maintain (e.g., by being more subject to mutation pressure), then weak biases are the inevitable consequence. This is surprising given previous work on the evolution of learning, which suggests the opposite: that learning can make evolution of innate constraints more likely.

To demonstrate this integrated approach, we apply the biocultural framework to three case studies targeting different language facets: (i) Vocal production learning (VPL), the ability to modify vocalizations based on experience; (ii) language structure, the systematic relations between linguistic elements; and (iii) social underpinnings, the behaviors enabling cultural transmission. These are illustrative, not exhaustive, facets chosen to demonstrate the framework's utility.

Case Study 1: Vocal Production Learning. While human language is inherently multimodal, speech is the primary modality across societies when available. Its acquisition depends critically on auditory-guided vocal production learning (VPL), defined as the ability to flexibly modify and expand one's vocal repertoire based on auditory experience. This capacity is foundational for learning the sounds and open-ended vocabulary of a spoken language. Although nonhuman primates show limited VPL, it has emerged convergently in birds, bats, cetaceans, pinnipeds, and elephants. Growing evidence suggests these independent evolutionary events may involve deep homology, where convergently evolved traits recruit similar underlying genetic regulatory networks across species. This supports the idea that language facets build on ancient genetic and neural infrastructures, modified for new functions.

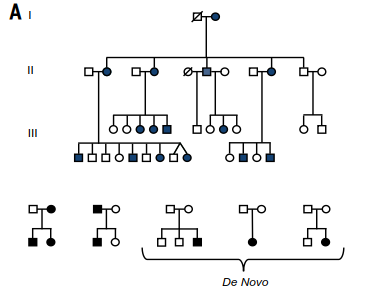

The relevance of deep homology is exemplified by research on the FOXP2 gene. Initially identified through studies of hereditary developmental speech and language disorders (28), this gene was linked to childhood apraxia of speech in the well-studied "KE family" (Fig. 2A). Disruptions in FOXP2 consistently lead to developmental speech deficits. Cross-species comparisons reveal FOXP2 is evolutionarily ancient, conserved in vertebrates from fish to mammals, and active in brain regions like the basal ganglia, cortex, and cerebellum. This deep conservation implies its role in human speech is built upon ancient pathways for motor-skill learning and vocalization.

Fig. 2. Investigating evolution of vocal production learning with tools of molecular genetics: FOXP2 as an example. (A) The starting point was a three-generation family, the KE family, in which half of the relatives (shaded symbols) were affected by a neurodevelopmental disorder primarily involving childhood apraxia of speech, accompanied by expressive and receptive language deficits (top). The affected relatives carried a change of one DNA letter (nucleotide) in the FOXP2 gene. This small change in DNA alters the amino acid sequence and, hence, the shape of a key part of the regulatory protein that FOXP2 encodes, stopping it from functioning in its normal way. Advances in DNA sequencing led to identification of >28 additional individuals (from 17 families) carrying different pathogenic single-nucleotide variants of FOXP2, with problems in speech development being the most common feature found in these cases. As shown in the bottom of the panel, although pathogenic variants were sometimes inherited from affected parents, in many of the cases, they arose de novo in children with unaffected parents.

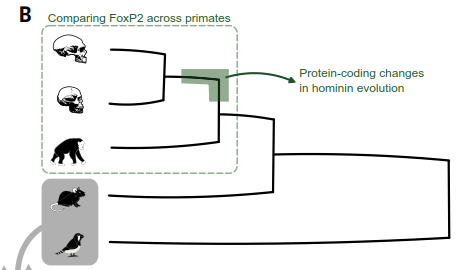

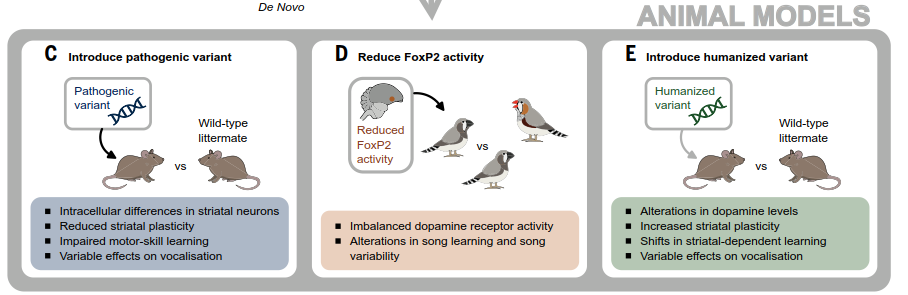

Research using animal models has been highly revealing. Genetically engineered mice carrying human FOXP2 disruptions exhibit motor learning deficits and altered neuronal properties (Fig. 2C). Studies in vocal-learning songbirds are particularly instructive. In juvenile male zebra finches learning song, the avian FoxP2 shows elevated activity in Area X, a basal ganglia structure essential for VPL. Reducing FoxP2 activity in Area X impairs song learning and variability, linked to disturbed dopaminergic signaling (Fig. 2D). This indicates the gene's impact on brain plasticity for sensorimotor learning was independently recruited for VPL in disparate lineages. Recent genomic analyses across over 200 mammals have further identified additional genetic loci associated with VPL.

(B) Comparisons of DNA sequences across different species (comparative genomics) identified versions of FOXP2 in distantly related vertebrates, including mammals, birds, reptiles, fish, and amphibians, showing that the gene has a deep evolutionary history. Against this background, integration of findings from extant apes and extinct archaic hominins revealed that changes in the amino acid sequence of the encoded protein occurred on the Homo lineage after splitting from the common ancestor of chimpanzees and bonobos.

(C) Researchers engineered mouse models that carry the same pathogenic variant that causes speech problems in the KE family. Investigations of these mice reported motor skill learning deficits, reduced plasticity in the striatum (part of the basal ganglia), disturbed intracellular “protein motors” in striatal neurons, and loss of neuronal homeostasis in deep- layer cortical neurons, among other findings.

(D) Moving to songbirds, lentivirus-mediated RNA interference has been used to reduce activity of FoxP2 (the avian equivalent of FOXP2) in Area X, a key nucleus in the basal ganglia of male zebra finches. Such studies uncovered effects of the gene on song learning and the control of song variability, potentially mediated by changes in dopaminergic signaling.

(E) When researchers used genetic manipulations to introduce hominin amino acid substitutions of FOXP2 into mice, they observed regional changes in dopamine levels and increased plasticity in the striatum. Motor skill learning and vocal behaviors of adult male mice were unaffected according to one study, but later investigations of female and male vocalizations in social contexts found that the partially “humanized” mice used higher frequencies and more complex syllable types. Another study of these mice uncovered different patterns of striatal- dependent stimulus-response association learning. Overall, this suite of human and animal model studies shows how genes involved in VPL can be empirically investigated across species to give new insights into evolutionary pathways.

The study of ancient DNA provides a transformative data source. Sequencing genomes of Neanderthals and Denisovans—archaic hominins who shared a common ancestor with modern humans ~600 kyr ago — allows identification of genetic changes on the human lineage. For FOXP2, two amino acid changes occurred on the Homo lineage between 6 million and 600 thousand years ago. Introducing these ancient hominin variants into mice affects vocal behavior and basal ganglia function (Fig. 2E), showcasing a method to test the functional impact of evolutionary genetic changes relevant to language facets. Importantly, evolution also acts through regulatory changes. Many human-specific genetic differences may lie in regulatory elements controlling when and where genes are active. For instance, FOXP2 shows human-specific expression in brain immune cells called microglia. Paleoepigenetic techniques reconstructing chemical markers like methylation from ancient DNA have revealed regulatory differences between modern and archaic humans, some affecting genes related to the face and voice.

Further insights come from developmental studies of behaviors like babbling. This self-initiated vocal play in human infants is a cornerstone of spoken language acquisition. Analogous subsong occurs in juvenile songbirds, parrots, and vocal-learning bats, but is rare in species lacking VPL. Notably, deaf infants exposed to sign language from birth engage in manual "babbling", highlighting language's multimodality. Deaf infants also vocal babble, but without auditory input, it does not progress normally, illustrating the essential interaction between biological preparedness and environmental input.

Babbling and subsong are self-rewarding activities, not driven by immediate external reinforcement. This implies biological preparedness for VPL includes an endogenous reward system that makes vocal practice intrinsically rewarding. In songbirds, the sensory phase of memorizing song templates involves endogenous reward, as juveniles selectively attend to conspecific song. Subsequent sensorimotor practice correlates with neural activity in reward pathways, and blocking dopamine receptors impairs learning. While social reinforcement later shapes these behaviors (see Case Study 3), the early self-reinforcing stage is crucial for generating the raw material for learning. Thus, the evolution of VPL likely involved changes in both motor learning circuits and the neural substrates of endogenous reward.

Date added: 2026-02-14; views: 3;