Case Study 2: The Emergence of Linguistic Structure

Human language is defined by its intricate and systematic structure at multiple levels, enabling productivity where the meaning of complex expressions is composed from their parts (e.g., "cat" to "cats"). This combinatoriality—the recombination of units like sounds into words and words into sentences—is a foundational feature. While the neural correlates of structure are actively studied, a central unanswered question is how such systematicity initially arose. Research over the past 25 years employs experimental, computational, and observational methods to investigate how cognitive pressures and communicative needs shape structure through cultural transmission. Language must be both learnable by new generations and functional for interaction, driving the evolution of its systematic form.

Insights come from real-world cases of language creation, such as homesign systems developed by deaf individuals without sign language exposure, and emerging sign languages like Nicaraguan Sign Language (NSL). Studying these systems reveals how structure evolves from individual innovation to communal convention. Cross-cultural studies of child homesigners in the US, China, Turkey, and Nicaragua show that certain structural properties, like consistent gesture order (e.g., "grape-eat"), emerge independently, suggesting shared human cognitive biases (Fig. 3). Other features, like a stable lexicon, require a community to emerge, and more complex elements, such as using space for reference, develop only after transmission to new learner cohorts (NSL2). This progression highlights the respective roles of biological preparedness and cultural evolution.

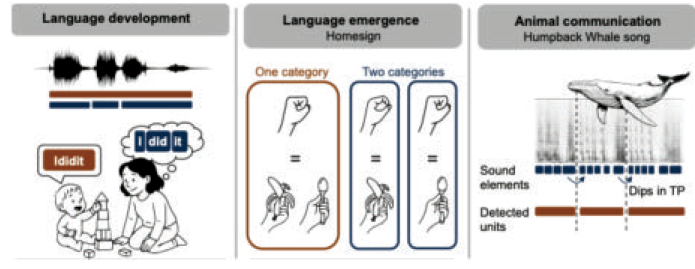

Fig. 3. Finding the right units. One of the challenges in studying communication in children and nonhuman animals is zeroing in on the right unit of analysis. This is challenging because the units we use to code data are influenced by hypotheses [explicit or implicit], often based on our own categories. For example, when we describe early child language, we typically attribute individuated words to the child (left). But we might be wrong; a child might use a larger unit, treating several words as a single “chunk”. Infants extract single word units from the speech they hear, but they also extract larger units containing more than one lexical word .

In fact, starting from larger units plays an important role in learning linguistic structure, particularly in learning grammatical relations between words, and in creating linguistic structure. One way to validate the categories we use is to find systematic patterns based on those categories, providing indirect evidence for the categories and also for their level of representation. For example, using semantic roles (patient, act, recipient, etc.) to categorize homesigners’ gestures results in systematic orderings (patientact, patient-recipient, and act-recipient), which validates coding at this level. But sometimes our coding system fails to produce systematic patterns.

This may be the time to scrap the system and start again, coding at a level smaller than the one previously used (middle). For example, homesigners could vary thumb-to-finger distance so that the handshape in the gesture for banana grasping is distinct from that in the gesture for spoon grasping (as they are when these objects are actually grasped). Alternatively, homesigners could use the same handshape in both gestures, introducing one larger category for grasping objects <1 inch in diameter. To discover the homesigner’s categories, we need to code in units that are smaller than the units on which those categories are based; otherwise, the categories may be created by us, not the child.

When we seek the right units in nonhuman communication [e.g., gestures in great apes], the challenge is greater because we have limited insight into the categories relevant to nonhuman animals and must validate the categories in the animal itself [e.g., by using playback experiments,]. Nonetheless, the approach of seeking out coherent patterns can also help reveal units in animal communication (right). For example, using transitional probabilities (TP) between syllables to segment humpback whale song [a cue used by human infants to segment speech] uncovered statistically coherent subsequences whose frequency distribution followed a particular power law also found in all human languages.

This points to a notable similarity between two evolutionarily distant species (whales and humans), united by having culturally transmitted communication systems. Debates about how to detect the appropriate units continue, with new perspectives coming from machine learning. In general, allowing for units at multiple levels of representation provides insight into structure in child language, homesign, and animal communication.

A key finding concerns the segmentation of complex ideas. Early NSL signers often conveyed motion events (e.g., a ball bouncing down) holistically, expressing path and manner simultaneously. Later cohorts systematically segmented these concepts into separate, recombinable elements, enhancing combinatorial flexibility. Laboratory experiments using iterated learning paradigms—where a participant learns from a previous participant's output—mirror this finding. When participants communicate using only gesture, holistic signals become progressively more segmented and systematic over simulated generations, demonstrating how learning and transmission pressures drive structural emergence. This aligns with holistic protolanguage theories, where systems originate as unanalyzed wholes that are gradually broken into constituent parts.

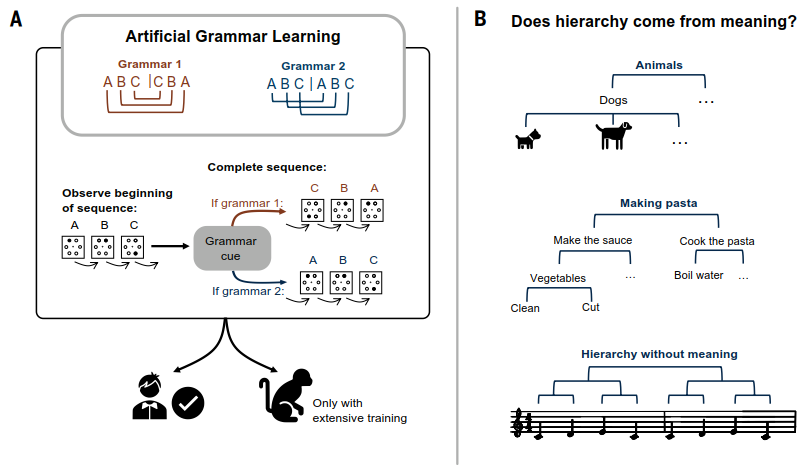

This whole-to-part analysis is also evident in first language acquisition, where children decompose phrases like "Ididit" into "I did it". Computational simulations further allow testing of learning biases that may differ from modern humans. A critical open question is identifying uniquely human cognitive capacities, such as "dendrophilia"—a domain-general bias to infer hierarchical tree structures from sequential data (Fig. 4). Research using animal models helps dissect the roles of biology and culture. Songbirds, as vocal learners with culturally transmitted songs, exhibit combinatorial structure in their vocal sequences. Iterated learning experiments with isolated zebra finches show that transmitted isolate songs converge within generations onto well-structured, species-typical songs, underscoring transmission's role in structural elaboration.

Fig. 4. The origins of hierarchical structure: Dendrophilia or semantics? An open question for the field concerns which, if any, capabilities underlying language are specifically enhanced in humans. One component hypothesized as highly developed in humans and weak or absent in other species is “dendrophilia,” a domain-general proclivity to infer tree structures from data whenever possible. Dendrophilia combines a domain-general capacity to perceive hierarchical structures in stimuli with a strong preference to encode data into hierarchical structures.

(A) This preference is often studied using Artificial Grammar Learning (AGL) experiments, where learners are exposed to sequences of stimuli whose appearance is governed by an underlying hierarchical grammar. If learners deduced the grammar, then they should be able to complete sequences in a way that conforms to it. Considerable experimental evidence from cross-species AGL research supports dendrophilia as being both highly developed and biologically canalized in humans and reduced or absent in other species studied to date. For example, a recent study found that, with adequate time and a consistent exogenous reward structure, macaque monkeys can learn hierarchical structures based on meaningless spatial or motor sequences, but learning required many months and tens of thousands of rewarded trials. By contrast, preschool children learn these same systems rapidly, in as few as six trials, with few or no errors. The presence of some hierarchical structure in homesign (case study 2) offers further evidence of biological preparedness for dendrophilia in our species. However, the finding that linguistic structure emerges gradually over generations indicates that cultural transmission is important for explaining hierarchical structure in fully developed languages (as for birdsong). Some precursor(s) of dendrophilia may be present in the motor and/or social domain in other primates, such as the perception and processing of complex dominance hierarchies, as shown in baboons and other socially complex species.

(B) The problem of acquiring and using treelike structures may be greatly reduced in contexts involving signal or meaning pairs (as in human language). If semantics already possess hierarchical structure and signals are mapped onto this hierarchical meaning space, then it may strongly bias the learner to impose or perceive tree structure in the signals themselves. Notably, the existence of hierarchical structure in human music or similar systems, such as bird or whale song, where signals do not map onto highly structured meanings, suggests that compositional semantic mappings are not necessary (or solely responsible) for hierarchical structure to emerge. Similarly, in AGL experiments, humans readily perceive hierarchical structure in meaningless visual strings. Better understanding of the neural mechanisms involved in structural learning and innovative new methods to “tweak” reward structures in animals can shed light on origins of hierarchical structure not just in language but also other domains, such as music and art.

Conversely, nonhuman primates largely lack culturally transmitted communication, though some combinatorial vocalizations exist. Crucially, experiments with baboons demonstrate that systematic structure can emerge even without species-specific biological preparedness for cultural transmission. When baboons are exogenously rewarded for copying visual patterns in an iterated learning chain, structured patterns emerge over iterations. This shows that external rewards (analogous to endogenous rewards in humans) can facilitate systematicity. Together, these studies illustrate that the emergence of linguistic structure is not reliant on a single factor but results from the interaction of domain-general learning biases, communicative pressures across generations, and species-specific biological preparations supporting cultural transmission.

Date added: 2026-02-14; views: 3;