Sea Ice. Types of Ice. Distribution of Ice

Types of Ice. Two types of ice are commonly found in the world ocean. The first type is glacial ice which is formed in the vast ice sheets that cover Greenland and Antarctica. The ice is transported to sea to drift as icebergs over great distances before melting- The second type is sea ice and is the result of the freezing of seawater in cold climates

The formation of sea ice depends primarily on the surface salinity, vertical salinity distribution, water depth, temperature, winds, currents, and sea state. Because of these factors sea ice can take on a number of forms and physical properties. For example, with a calm sea state and rapid cooling the sea surface is frozen into a clear, uniform sheet of ice.

When waves disturb the sea surface, ice crystals are disturbed by the shearing water motion; a solid ice sheet cannot form, and instead, individual ice crystals form thin plates that have a more or less vertical orientation. Under these conditions the sea surface appears slushy or soupy and is called grease ice and slush ice. Further freezing with continued water motion results in the formation of flat disks 30-100 cm in diameter called pancake ice.

These forms represent early stages in ice formation. As freezing continues a solid ice sheet is formed that when young may be 2 to 3 cm thick, but may increase over the winter to 2 to 3 m thick. In shallow water along coastal regions ice sheets are called fast ice.

Under the influence of winds and currents ice sheets are broken up and drift extensively. Pieces of drifting ice undergo many transformations. They often collide, freeze together, break up, pile up, and are placed under great stress by winds and currents. Pack ice is the name given ice sheets that have been piled up, sometimes to thicknesses exceeding 20 m. Pack ice covers large areas of the Arctic and Antarctic oceans.

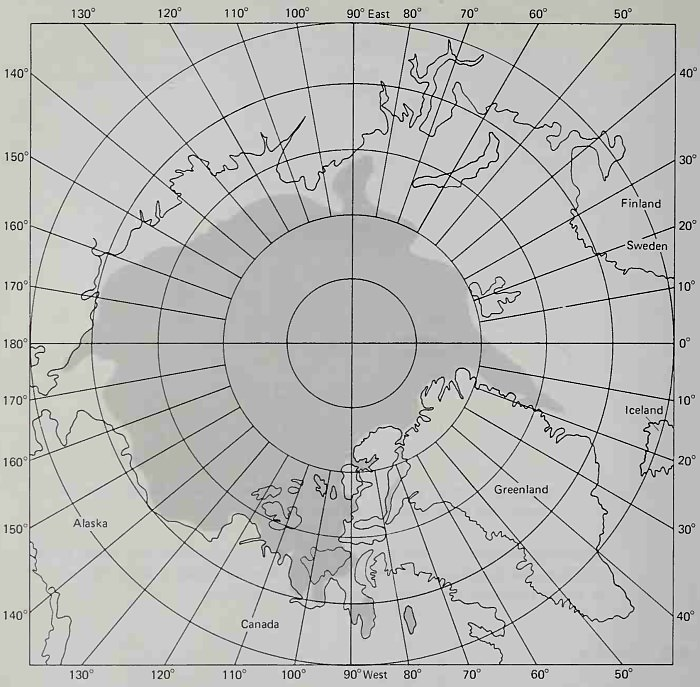

Distribution of Ice. The distribution of ice in the polar oceans varies seasonally; however, vast regions are covered throughout the year. In the Arctic Ocean permanent ice covers about 70 percent of the ocean basin and is concentrated primarily in Siberia and North America (Fig. 6-14). This ice cover is called the polar ice cap. Ice rarely forms around the western coast of Norway because of the existence of the relatively warm North Atlantic Current and Norwegian Current that flow along those shores (see Fig. 8-3).

Figure 6-14. Mean ice conditions, September 1 to 15. (After H.O. Pub. No. 705, U.S. Naval Oceanographic Office, Washington, D.C.)

During the winter months packed ice extends southward along the Greenland coasts and the eastern side of North America. This winter ice distribution and its subsequent melting back between March and July give rise to great numbers of icebergs that drift southward along the Labrador coast and the Grand Banks of North America. These icebergs are navigations hazards. In 1913 (after the sinking of the Titanic due to a collision with an iceberg) the U.S. Coast Guard formed the International Ice Patrol Service to chart the occurrence and drift of major icebergs in the sea lanes.

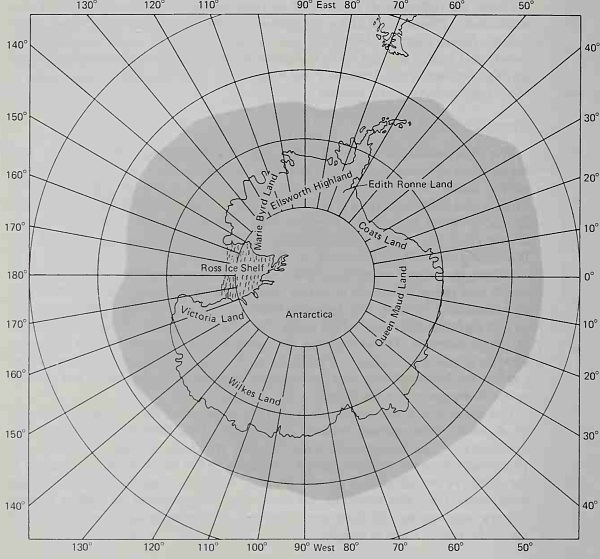

The ice in the Antarctic Ocean is distributed around the Antarctic continent in a nearly symmetrical pattern (Fig. 6-15). This distribution reflects the symmetry of the circumpolar currents and the zonal climatic patterns; the permanent ice pack extends almost uniformly to 60° south latitude. Because of the massive accumulation of ice on the Antarctic continent, the icebergs originating from the Antarctic ice sheet can be enormous. In 1953 a tabular iceberg was sighted off Antarctica that rose 30 m above sea level and was 40 km wide and 145 km in length.

Figure 6-15. Mean ice conditions, October. (After H.O. Pub. No. U.S. Naval Oceanographic Office, Washington, D.C.)

Formation and Composition of Sea Ice. The properties of sea ice depend on a number of factors that include the rate of formation and the chemical composition of the original seawater. As discussed in Sec. 6.2 and shown in Fig. 6-4, the initial freezing point of sea ice for 35%o seawater is —1.9°C. The first ice crystals to form are pure water and are needlelike or platelike in appearance. The crystals eventually join together forming cavities trapping the brine that existed between the ice crystals. The size of the cavities and hence the amount of brine that is trapped within the ice crystal network depends upon the speed of ice formation. The slower the ice forms the larger the water crystals and the smaller the cavities.

This mode of formation (that includes initial crystals of pure water and subsequent trapping and freezing of seawater) leads to the observation that the salinity of sea ice is always less than the salinity of the original seawater from which it formed. Analysis of many sea-ice samples shows that the freezing of seawater with a surface salinity of 30%o leads to sea ice whose salinity may vary from about 5.6%o to 10.2%o depending on the rate of freezing. The density of this sea ice is approximately 0.92 g per cu cm.

Date added: 2024-04-08; views: 587;