Food Safety Assessment. Determination of Toxic Materials

A. Determination of Toxic Materials. When a whole food, component of a food, or a toxicant known to be in a food has to be analyzed and determined for safety, the food toxicologist must proceed with a number of steps. The questions of what known toxicant(s) is present, its concentration, population exposure, acute and chronic toxicity, and possibly a way to eliminate or detoxify the toxicant(s) must all be addressed.

Food toxicants are usually always present in very low amounts because chemicals with any significant level of toxicity are rejected as foods. People develop a distaste for food after it is associated with any episodes of illness.

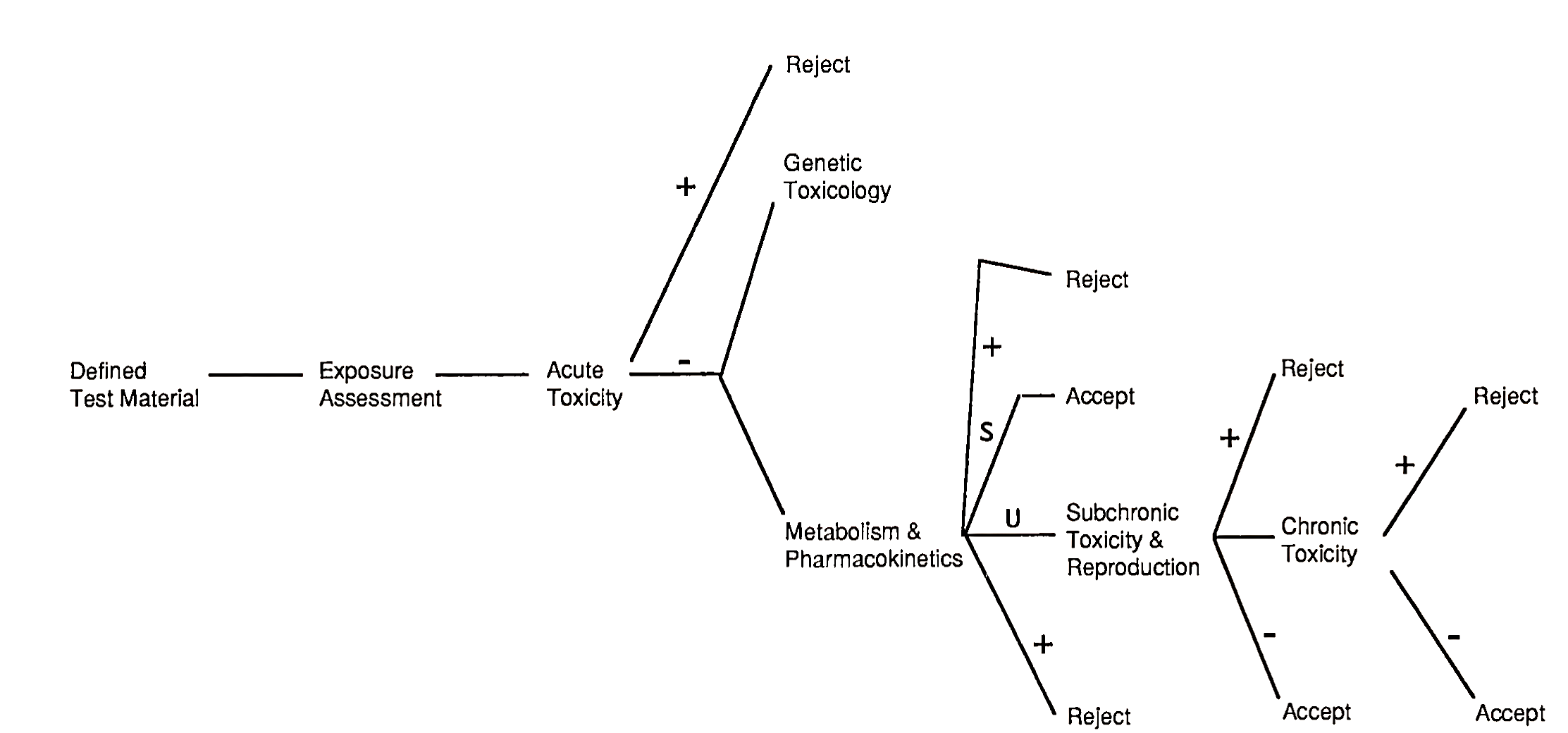

A decision tree protocol, used to determine whether there exists an unacceptable or acceptable risk after each testing step of food components, has been proposed by a Scientific Committee of the U.S. Food Safety Council. A summary of this protocol is presented in Fig. 1. Other similar kinds of decision trees regarding (1) the safety evaluation of whole foods, (2) single chemical entities, and (3) food ingredients derived from genetically modified microorganisms have been made by the International Food Biotechnology Council. Numerous modifications have and will continue to occur, but these decision tree concepts have strong support from the scientific community.

FIGURE I. Decision tree protocol. The defined test material is a specific food chemical or component. The component may be rejected, because of unacceptable risks, after each testing stage. +, socially unacceptable risk; —, does not present a socially unacceptable risk; S, metabolites known and safe; U, metabolites unknown or of doubtful safety

The analysis of toxicants requires both an assay for detecting the toxic material and a method for separating it from the rest of the complex food matrix. Identification of unknown chemicals has dramatically improved since the development of analytical instruments such as ultraviolet, infrared, nuclear resonance, and mass spectroscopy. Additional analytical techniques specific for trace element toxicants are discussed in Section III. Food toxicant analysis essentially goes through four steps: (1) proper sampling; (2) extraction; (3) cleanup; and (4) chromatography.

B. Toxicity Testing. 1. Acute toxicity is defined as the adverse effects occurring within a short time of intake of a single dose or multiple doses within 24 hr. Groups of laboratory animals, usually rats or mice, can be given one dose to observe the quantal or “all or none” response, or multiple doses to study the “graded response.”

Mortality and overt toxicity signs are examples of quantal data, whereas enzyme activity, hematology data, and body weight are quantitative parameters observed in a short-term graded response. The LD50 is a statistically derived single dose of a substance that can be expected to cause death in 50% of a group of animals. It is actually not a biological constant but a statistical term designed to describe the lethal response of a compound in a particular population under a specific set of experimental conditions. In essence, the dose-response curve, the time to death, toxicity symptoms, and pathologic findings are all vital and perhaps even more critical than the LD50 in the evaluation of acute toxicity.

2. Subchronic toxicity tests are studies of food toxicants designed to last usually for 90 days but can extend to 1 year. These tests are designed to determine responses produced by low-dose repeated exposure of a substance to a test animal. The substance can be administered to groups of animals by gavage, drinking water, or directly mixed into a defined diet. Three to four doses of the material should be given to 10-20 rodents per each sex per dose group. In general, not more than 10% of the animals in the high-dose group should die within a 90-day study, and no deaths should occur within the lower-dose groups. The usual observations and evaluations are: daily observations, periodic physical examinations, monitoring body weight and food consumption, and analyses of hematology, biochemistry, and urinary parameters. When the animals are killed at the end of the study, organ weights are recorded and a histopathologic evaluation is performed.

3. Chronic tests are long-term studies that are designed to test relatively low-level exposure of a food toxicant. The studies are designed to detect the origin of any adverse response regarding the animals’ structural and functional entities. They determine the margin of safety between the substance’s use or presence in a food and toxicity. Chronic studies, usually measured in years depending on the experimental animal, test the tumor induction or carcinogenicity potential of a substance. Generally the food toxicologist needs the assistance of an experienced animal pathologist for both routine and special pathology in differentiating between degenerative or atrophic changes of tissues and normal variations.

To learn why a chemical is carcinogenic and to provide an improved basis for estimating human risk, it is required to perform absorption, distribution, and excretion studies of the substance and its metabolites. Specific protocol directions and suggestions for carcinogenicity testing and monitoring continue to be the subject of numerous reviews by individuals, expert panels, and government agencies.

4. Teratogenesis testing is done to observe possible embryonic developmental abnormalities from a food toxicant. The human fetus is most susceptible to anatomical defects at about 30 days of gestation, that is, during organogenesis. Thus, teratogenesis studies in animal models should include 1- to 2-day treatments during their particular organogenesis time frame, as well as continuous treatment during gestation. In addition, tests of reproductive toxicity may include treatment of both males and females prior to mating, treatment of females through lactation, and continued testing of the offspring.

5. Genetic testing is done to determine if the substance induces mutation or inheritable changes in the genetic information of the cell. The decision tree approach (see Fig. 1) proposes a battery of genetic tests early in the testing scheme. Certain mutagenic substances are also carcinogenic. Point mutations (localized changes in DNA) and frame shift mutations (DNA base pair additions or deletions) of substances have been tested for many years by the Ames assay.

This assay is accomplished by a specially constructed strain of Salmonella typbimirium bacteria. There are many other microbial organisms as well as mammalian cell lines used in various kinds of mutagen tests. Macrolesions, that is, structural and/or numerical changes in chromosomes, are also studied using cytological analysis. In the future, genetic testing will probably be done with the use of cultured human somatic as well as germ cells. Damage to germ cells has the important potential for transmission to the next generation.

Date added: 2023-01-09; views: 625;