Natural Toxicants. Animal Tissue. Marine Animal Tissue

A. Animal Tissue. Outside of reports of toxic quail meat, as described in Section I, and vasoactive amines produced by bacteria on putrefying meat, there is not a great deal of evidence of natural toxicants in mammalian or avian species. However, there are toxins in animal liver that have produced toxic responses when consumed to an excess by animals and humans. For centuries Asiatic people have used dried bear liver as a folk medicine due to its tranquilizing and pain-killing effects. Bile acids, mainly cholic acid, synthesized in the liver can act as a suppressant on the central nervous system. Beef and other animal livers eaten in the United States do not contain sufficient quantities of bile acids to produce such effects.

Vitamin A is an essential vitamin necessary for normal growth and vision. However, it is toxic to humans when ingested in excess of 2 million International Units (IU). Polar bear liver contains about 1.8 million IU of vitamin A per 100 g of fresh liver. Early in the twentieth century, explorers in the Arctic and their dogs experienced various symptoms of joint pains, swelling, bleeding lips, and some fatalities. This was later shown to be a toxic syndrome from extreme levels of vitamin A intake when polar bear liver was consumed.

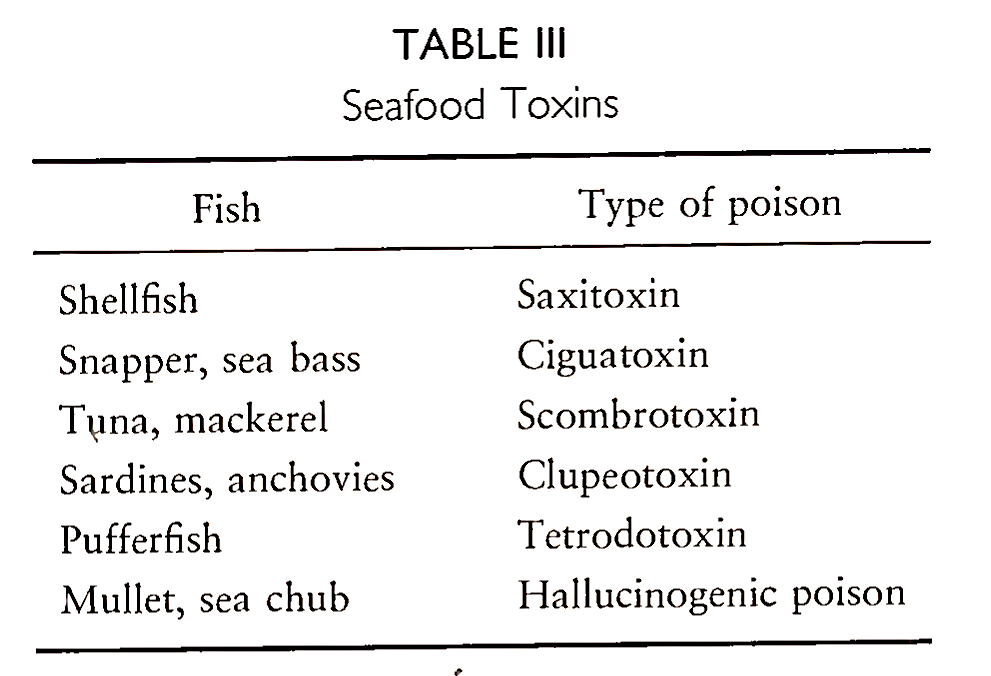

B. Marine Animal Tissue. Fish toxins are of two types, oral biotoxins when the fish is eaten and the large molecular venoms that are injected by specialized venom apparatus. Food toxicologists are concerned with toxic marine flesh from fish termed ichthyosarcotoxic fish. Widely consumed fish that can exhibit various types of poisons, depending on numerous but not completely known factors including environmental changes in their food chain, are listed in Table III.

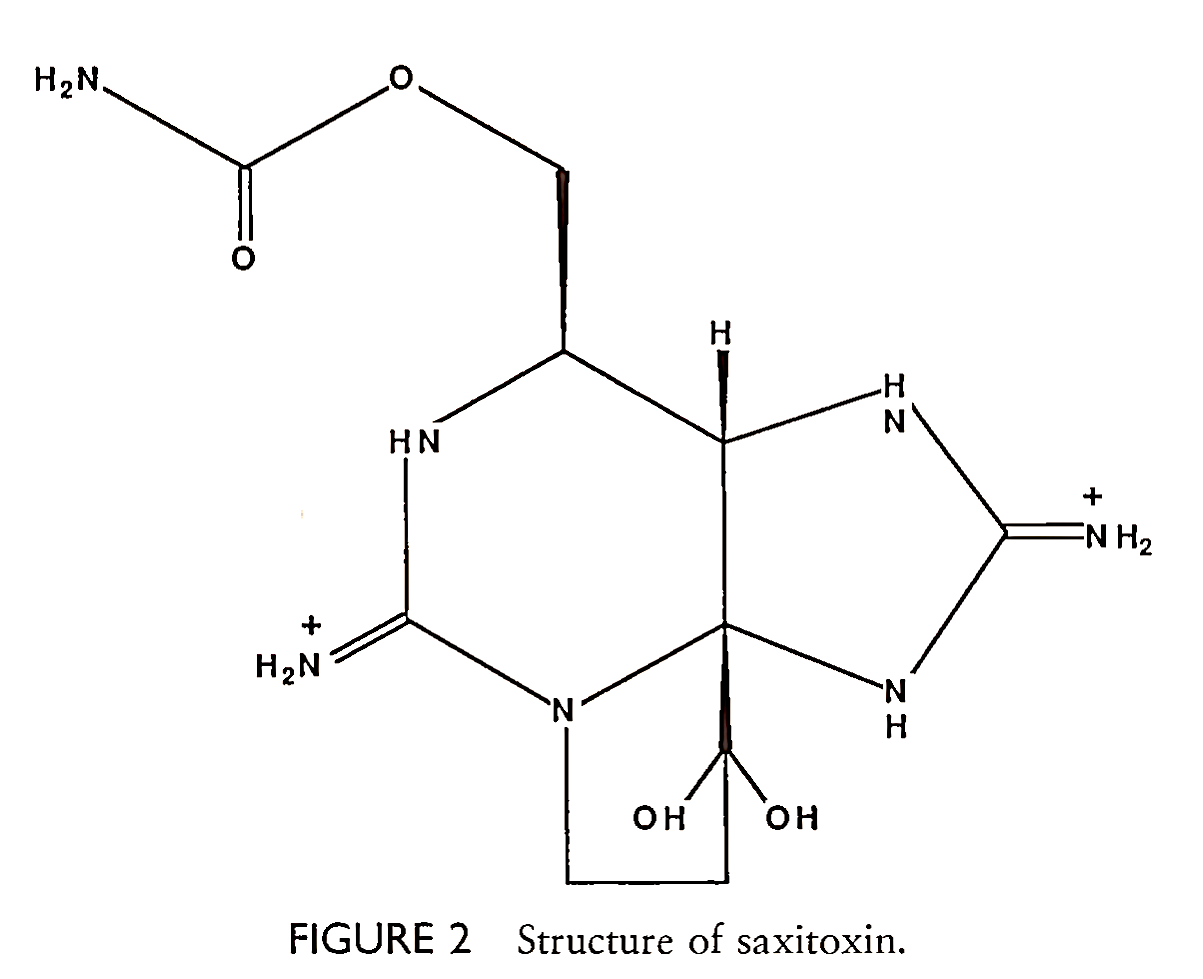

I. Saxitoxin. Clams, mussels, and other shellfish feeding on certain species of marine algae or dinoflagellates, especially Gonyaulax spp., accumulate a potent toxin known as saxitoxin (Fig. 2). This compound was first isolated in pure form in 1954 from California mussels and the Alaska butter clam. At certain times, depending on water temperature, pH, and other factors, the dinoflagellates grow rapidly.

At a concentration of about 20,000 cells per milliliter of seawater, the water appears brownish-red in color and is called red tide. The shellfish do not appear to be harmed by consuming the poisoned algae and slowly excrete the toxin. However, people eating such shellfish develop a serious condition of paralytic shellfish poisoning. The amount of this neurotoxin required for sickness and death in humans varies considerably and seems to indicate a tolerance to the poison from continuous intake of small doses.

Symptoms of paralytic shellfish poisoning begin with a numbness in the lips, tongue, and fingertips (paresthesia) that is apparent within a few minutes of eating the shellfish. This is followed by numbness in the legs, arms, and neck, with muscular incoordination (ataxia). Death results from respiratory paralysis within 2-12 hr after the dose. If one survives 24 hr, the prognosis is good with no lasting effects. FDA has regulated the poison to a maximum allowable level in all seafood products of 80 /xg/100 g.

2. Ciguatoxin. Besides snappers and sea bass, as indicated in Table III, there are upward of 400 fish species that possess ciguatoxin. It is also associated with fish consuming dinoflagellates, especially Porocentrum spp. in tropical or warm, temperate-zone reefs. Evidence indicates that the primary cause of this toxicity is bacteria living on these and other dinoflagellates, but ciguatera poisoning is not a form of typical bacterial food poisoning. It is usually never fatal, but neurological symptoms of extremity paresthesias, ataxia, muscle pain, and weakness are almost always observed. There are no accurate statistics worldwide as to the incidence rate of ciguatoxin poisoning. Recovery can take from 2 days to years. There is no way to detect a ciguatoxic fish by appearance, since freshness has no bearing on toxicity, and cooking does not destroy the toxin. Targe predatory reef fish should be eaten with caution.

3. Scombrotoxism. Scombrotoxism is caused by the improper preservation of scombroid fish, such as tuna and mackerel, whereby various bacteria act on the fish muscle histidine to form histamine. It has also been called histamine poisoning and is detected by a very sharp or peppery taste. Symptoms usually last for a few hours and include dizziness, cardiac palpitation, rapid pulse, and abdominal pain. There is danger of shock. To prevent poisoning, prompt fish refrigeration or consuming the fish soon after capture is necessary.

4. Clupeotoxism. Clupeiform fish (i.e., sardines, herring, and anchovies) in tropical island areas feeding on toxic dinoflagellate blooms produce clupeotoxin, especially in the viscera. The actual source and nature of the poison have never been identified. Symptoms of the poisoning are usually violent, with the indication of a sharp metallic taste on the first taste of the fish. Tachycardia, cold and clammy skin, and a drop in blood pressure, following by various neurological disturbances, rapidly ensue.

Death may occur in 15 min. The fatality rate is very high. Pruritus and various types of skin eruptions have been reported in victims who have survived. Clupeotoxism has been related to ciguatera poisoning, because of initial similar symptoms, but this has never been documented.

5. Tetrodotoxin. Tetrodotoxin from pufferfish is the major cause of food intoxications in Japan. The sale of toxic puffers is regulated carefully, as this toxin is one of the most violent forms of marine biotoxications. There has been a great deal of research accomplished on this toxin and the mechanism of action is known. No cooking or drying procedure controls the poison.

6. Hallucinogenic Poison. Certain types of reef fish in the tropical Pacific and Indian oceans, such as mullet and sea chub, can produce hallucinogenic symptoms within minutes to 2 hr after ingestion. The poison primarily effects the central nervous system, but there have been no fatalities reported and the form of poisoning generally is mild. The nature of the poison is unknown and toxicity is very sporadic, somewhat uncommon yet unpredictable. The poison is not destroyed by cooking, and hallucinogenic fish cannot be detected by their appearance.

Date added: 2023-01-09; views: 777;