The guerrilla versus the phalanx habit

Extending the ‘explore versus exploit’ argument shows that an open architecture (longer spacers) would promote rapid invasion of new habitat, while a closed architecture (shorter spacers) would favor consolidation of acquired habitat. (This is conventionally depicted in terms of horizontal expansion but is equally true for vertical growth as represented for example by tightly or loosely packed canopies of corals and trees.)

For plants, the ecological implications have been recognized implicitly at least since Salisbury (1942, pp. 225-226) contrasted the aggressive vegetative spread of the creeping buttercup (Ranunculus repens) with the slow expansion of the figwort (Scrophularia nodosa). Lovett Doust (1981a) coined the terms ‘guerrilla’ and ‘phalanx’, reminiscent of military arrays, to describe distinctive clonal plant growth patterns (Table 5.3 and Fig. 5.6).

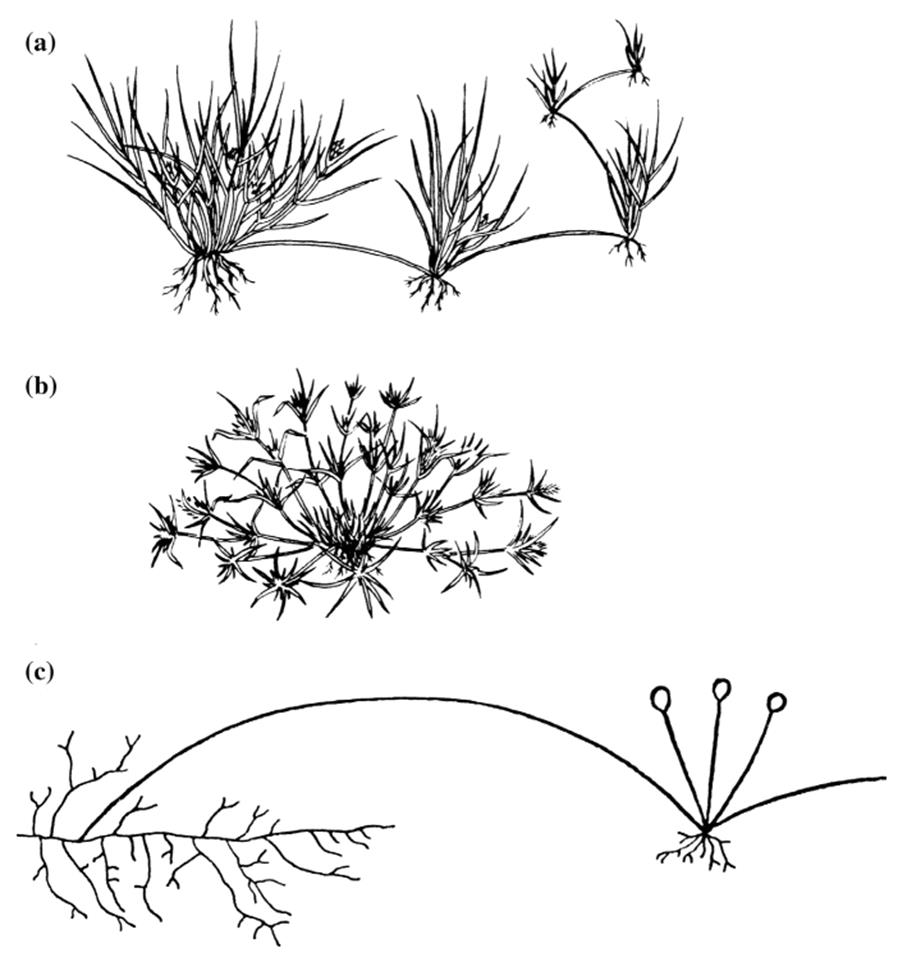

Fig. 5.6. Clonal morphology of sessile, branched, modular organisms as represented by plants and fungi. Compare with Fig. 5.7. a 'Guerrilla', or the extensive type with widely spaced ramets, shown by buffalograss (Bouteloua dactyloides). b 'Phalanx' or the intensive type with tightly packed ramets, shown by false buffalograss (Munroasquarrosa). From Silander (1985) based on terminology of Lovett Doust (1981a). Reproduced from: Population Biology and Evolution of Clonal Organisms, edited by Jeremy B.C. Jackson, Leo W. Buss, and Robert E. Cook, by permission of Yale University Press ©1985. c An aerial stolon of the zygomycete Rhizopus stolonifera ('black bread mold') has arisen from behind the advancing margin of a colony growing on nutrient agar. It has 'rooted' in an unexploited zone of medium and produced a new ramet distant from the original parental ramet. In this fashion and by the prolific production of asexual spores, Rhizopus rapidly colonizes bread and other substrata in guerrilla-like fashion. From Ingold (1965). Reproduced from: Spore Liberation by C.T. Ingold, by permission of Oxford University Press, ©1965

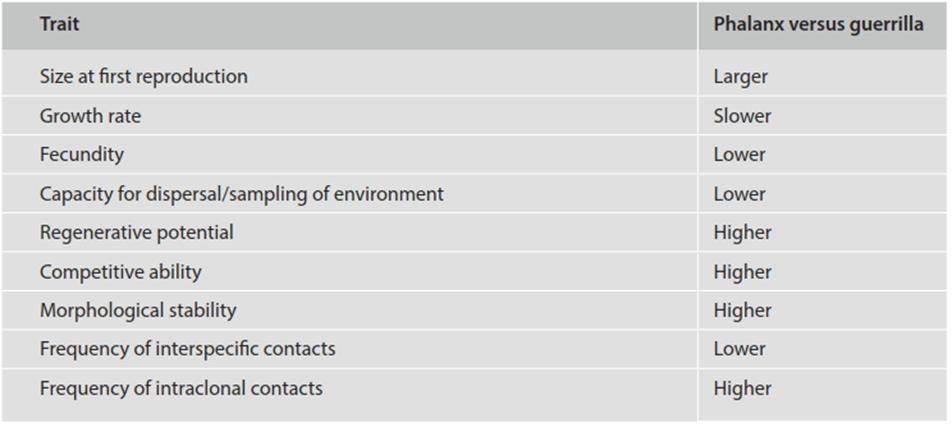

Table 5.3. Life history strategies of guerrilla and phalanx architectures (modified from Lovett Doust 1981a,b; Buss and Blackstone 1991)

The guerrilla architecture is characterized by long internodes, infrequent branching, spaced modules, and minimum overlap of RDZs. While this is characteristic of the creeping buttercup, Lovett Doust showed (1981 a, b) that local populations in grassland vs woodland vary in the extremity of guerrilla-like form. Other examples include white clover and strawberry. According to Lovett Doust (1981a), the guerrilla strategy maximizes interspecific contacts and sampling of the environment that, in a woodland habitat for example, would be advantageous to locate sunflecks in the understory.

Conversely, the phalanx arrangement is characterized by short internodes, frequent branching, and closely packed modules. Consequently space is densely occupied, contact is mainly intraclonal, and RDZs overlap. Plant examples include various tussock grasses such as Deschampsia cespitosa (Harper 1985) and the common golden rod (Solidago canadensis) (Smith and Palmer 1976). As suggested above, both phalanx and guerrilla species can adjust their architectures as a result of competition or in response to resource- rich patches (Lovett Doust 1981b; de Kroon and Hutchings 1995; de Kroon et al. 2005)

and there is evidence that such plasticity can be adaptive (Schmid 1986; van Kleunen and Fischer 2001; however, see Buss and Blackstone 1991; Ferrell 2008).

Date added: 2025-06-15; views: 198;